Télé et cinéma

La présence d’un « script editor »

Assurer la cohérence narrative est un grand défi. Principalement lors d’un changement d’auteurs. D’après nous, l’éditeur devrait avoir pour rôle d’assurer une transition harmonieuse, mais ce n’est pas le cas, car, le plus souvent, un nouvel auteur est l’occasion de relancer un titre, ce qui peut amener l’éditeur à accepter un changement de direction pas toujours élégant. Andrew Aardizzi émettait un commentaire très critique sur le travail de Mark Waid pour sa série Daredevil. D’après lui, l’auteur ferait table rase des plus récents événements et les dénierait même (« Episode 12: I Object! (to Mark Waid’s ‘Daredevil’) », www.comicbookdaily.com, 19 janvier 2012) .

La télévision offre une solution simple à un tel phénomène. Il est très rare qu’une série télé soit entièrement écrite par la même équipe d’auteurs. Un script editor verra à ce que les évolutions d’un auteur pour un épisode donné soient cohérentes avec la trame générale de la série.

Nous sommes actuellement dans la même situation. En effet, n’ayant pas assez de temps pour tout faire, nous avons préféré confier la rédaction des dialogues de certaines trames à un autre auteur. Nous veillons tout de même à vérifier son travail et à faire les ajustements nécessaires pour assurer la cohérence de notre récit.

Précisons que ce travail d’équipe à la rédaction est très enrichissant, car il permet de nombreux échanges, ce qui donne l’occasion d’approfondir notre réflexion sur les personnages.

Laisser le lecteur découvrir l’histoire : l’exemple la série The Wire

À partir de travaux universitaires, Terressa Lezzi commentait la série télé The Wire. Elle écrivait : « The result of this style was a show that allowed viewers the satisfaction of discovering the beauty of a story, instead of having it explicitly and repeatedly pointed out of them. » (« Why You Love The Wire, Explained in Fasciting Detail », www.fastcompany.com).

Marc Alan Fishman va un peu dans le même sens lorsqu’il affirme que les meilleures bandes dessinées sont celles qui prennent le temps de bien présenter leur concept en cinq ou six aventures (« How To Succeed in Comics Without Really Trying », www.comicbookdaily.com, 25 février 2012). Brian K. Vaughan va dans le même sens et affirme dans une entrevue qu’il n’avait pas écrit un dénouement fort à la fin de la première aventure de sa série SAGA (The Beat « Interview : Brian K. Vaughan on SAGA, Lost, Twitter and more », comicsbeat.com, 14 mars 2012). Nous sommes, naturellement, davantage en accord avec ce point de vue, mais nous verrons dans de prochains commentaires que d’autres analystes sont des partisans d’une approche plus directe.

L’Épreuve : une autre référence

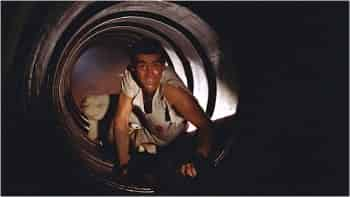

Nous avons déjà évoqué des scènes qui avaient inspiré notre aventure L’Épreuve. Il y a une référence supplémentaire dans le récit. Dans la scène où le Chinois et l’Indien s’enfoncent dans le tunnel pour disparaître, le jet de sang expulsé par l’ouverture est directement inspiré du film le Cube. Sans l’avoir vu au complet, nous étions tombés sur une scène similaire; elle nous avait tellement plu que nous l’avons intégrée dans une de nos aventures.

House of Cards comme source d’inspiration

La scène entre Valasquez et Shirley, à la fin de l’aventure « Payer la note », est librement inspirée du comportement de Francis Urquhart (joué par Ian Richardson) dans la série britannique Hourse of Cards. Tout en jouant double jeu avec ses proches collaborateurs, le personnage d’Urquhart avait l’habitude de leur demander leur pleine confiance tout en les intimidant physiquement. Valasquez n’est pas une copie de ce personnage, il est plus sombre, mais nous aimons l’idée du dévouement inconditionnel qu’Urquhart demande de ses propres collaborateurs. C’est ce dernier trait de personnalité que nous avons essayé de transposer à Valasquez.

Ne pas chercher à cacher ses références

Nous sommes continuellement bombardés de récits (télé, cinéma, journaux, livres, etc.). Inconsciemment ou même de façon parfaitement volontaire, nous empruntons des idées que nous avons vues ailleurs et les insérons dans notre récit. Ainsi, dans l’aventure, « L’épreuve », nous avons repris la scène du tunnel qui se réchauffe et de la grille électrifiée du film Doctor No. Peut-être que plusieurs avaient noté l’emprunt. Nous n’avons pas cherché à le camoufler; c’est pourquoi Jason y fait explicitement référence dans une de ses répliques.

Pourquoi des costumes?

Tony « G-Man » Guerrero, sur le blogue ComicVine, avait formulé une excellente question en novembre 2010 : « Pourquoi les vilains portent-ils des costumes? » Pour leur premier crime, on pourrait comprendre qu’il souhaite demeurer anonyme, mais, une fois qu’ils ont été capturés, le costume perd ce caractère d’anonymat. Pour notre part, nous résistons donc à l’objectif de donner un look fantaisiste ou trop sophistiqué à nos personnages. Nous souhaitons que leurs vêtements soient appropriés pour leur mission ou qu’ils servent à les distinguer socialement. À cet effet, nous avons apprécié ce souci de simplicité dans les costumes du film X-men First Class.

Le sacrifice des vilains

Plus jeune, il y a des scènes qui nous marquent. Dans le dessin animé Goldorak, à la fin de la première saison, l’un des principaux vilains, Hydargos, se sacrifie dans l’espoir de vaincre son adversaire et pour permettre à son supérieur de quitter le champ de bataille. Nous avons beaucoup aimé ce comportement et l’avons calqué, en quelque sorte, pour celui de Roslo dans le récit « Le sacrifice de soi-même. »

Voulons-nous jouer avec les flashbacks?

Un de nos lecteurs revient sur le lien qu’il existe entre la mort de Wally et le récit de son arrivée à l’Enceinte et nous demande si nous voulons imiter la série télé Lost, pour laquelle nous avons déjà exprimé notre admiration, par l’utilisation de flashbacks? Il s’agit d’une bonne question. Nous voyons une énorme différence entre notre trame temporelle et les flashbacks utilisés par les scénaristes de la série télé. Alors que, dans le second cas, le flashback sert principalement à nourrir un épisode, pour notre part, il est utilisé pour faire de nos différents récits une mosaïque dont nous espérons présenter toute l’étendue. Naturellement, pour préserver quelques zones de mystère à notre histoire, le moment de la diffusion des différents récits n’est pas révélé.

Damon Lindelof et Carlton Cuse

Nous venons de recevoir le bouquin Lost Encyclopedia, ce qui nous donne l’occasion d’exprimer à nouveau notre admiration pour cette série télé. De la culture populaire à son meilleur! Nous apportons cette précision, car des gens disent que cette série n’était pas aussi bonne que The Sapranos ou Mad Men. L’affirmation est exact, mais ces deux séries étaient diffusées sur des réseaux spécialisés et s’adressaient donc à des auditoires plus spécifiques que la série Lost était diffusée sur un réseau grand public et elle devait donc respecter certaines contraintes. Malgré cela, les deux producteurs exécutifs n’ont pas hésité à complexifier leur trame narrative, la rendant, du même souffle, plus dense et profonde. Ils ont su faire un bon dosage entre l’émotion et l’action. Ils ont truffé leurs histoires de références sans que le procédé n’en soit pour autant tape-à-l’œil. Nous ne parlons pas d’une série parfaite, et seul le temps nous dira si elle vieillira bien, mais, pour l’instant, nous parlons d’un excellent travail de scénarisation pour une production de masse

Pourquoi des méchants?

Nous revenons sur le concept de méchant. Nous sommes convaincus qu’à la base d’une bonne histoire il doit y avoir un conflit qui peut prendre différentes formes. Dans une schématisation simpliste, le conflit impliquera des bons et des méchants. Mais qu’est-ce qui nous permet de distinguer les deux groupes? Trop souvent, pour nous aider, on fera en sorte que les méchants s’habillent avec des couleurs foncées ou qu’ils fument. Mais celui qui a été identifié comme un méchant sait-il que ses actions sont mauvaises? Will Smith s’était fait vilipender pour avoir affirmé que Hitler n’avait pas conscience de faire le mal. Nous partageons cet avis, « le méchant » est profondément convaincu de réaliser de bonnes actions pour son bien-être personnel ou encore pour celui de ceux qui l’entourent. Nous avons déjà parlé des zones grises de la personnalité de nos protagonistes. C’est toute cette ambiguïté qui rend le conflit vraiment intéressant et qui avait d’ailleurs été superbement illustrée par la déchéance de Michael Corleone dans le Parrain II.