TV and movie

What to write when everything’s been said? (

We like reading about other writers’ creative processes. We came across this interview with Sam Esmail, the multitalented person behind the Mr. Robot TV series, in which he discusses his primary concern in plot development: “And I was hamstrung in the first season because I was like, well, this is really only the first act, I need this thing to happen, I need this plot, whatever, the hack thing to happen. Because for me, plot is always an excuse to explore characters. ‘Cause who cares? The plot is the same plot that we see in basically every movie and TV show. But how we tell that story, what choices these characters could make …” (Jen Chaney , Gazelle Emami and Matt Zoller Seitz. “Mr. Robot Creator Sam Esmail on How He Handles Criticism of the Show,” www.vulture.com, September 28, 2016).

This is especially interesting to read when paired with the following quote from Christopher McQuarrie, who’s had a long career as a screenwriter for the movies and, more recently, as a director. Here he talks about writing The Usual Suspects: “There’s a part of us that wants to see the bad guy get away, that wants to see this guy outsmart authority, and beat the system. That to me is when a movie is really good: when no one is an idiot. Early on in the development of the Suspects script someone asked me why Kujan was chasing this guy Keaton. What does he care? Did Keaton kill his partner? No, he’s just passionate about his job. You don’t have to be Vincent Van Gogh to be passionate about what you do […] So many movies use revenge as motivation for characters. But I think that, unless you’re analyzing the mindset itself, it’s a bad motivation.” (“Christopher McQuarrie Gets Verbal on The Usual Suspects,” cinetropolis.net, April 13, 2014).

These two quotes may come from different places, but together, they say something about how you can’t always approach characterization directly. Otherwise, verbalizing a character’s choices can take away the spontaneity and contradictions that are inherent to human behaviour.

The temptation to be pompous—Part II

Joss Whedon said that emotions were the main thing at stake in his movie Avengers: Age of Ultron, and that his source of inspiration was Godfather II. Joss Whedon’s track record is far too impressive for us to be giving him advice. But, if emotion is the main thread, then there was already a goldmine available within the story line itself, in the issue of descendants. Black Widow can’t have children because of her training. Neither can Bruce Banner, but for different reasons. Ultron considers Tony Stark his father, and Vision is in a way, his son. The Avengers stories that inspired the movie (Ultron Unlimited, Avengers vol. 3, issues 19-22) showed Ultron trying to collect a variety of mental schemas to recreate an artificial lifeform, where different points of view could be shared. In sum, we feel the film could have gone into greater depth of feeling instead raising the bar with the physical challenges needing to be solved (saving the world, again).

Have a plan, but leave room to manoeuvre

In a long essay, Javier Grill–Marxauch looks back at his experience as a writer for the TV series Lost (“The Lost Will and Testament of Javier Grill–Marxauch,” http://okbjgm.weebly.com/lost, 24 March, 2015). The essay contains so many interesting blurbs about ups and downs of the creative process that we wanted to share a few:

“[…] we were paving the way for the good ideas by coming up with a lot of bad ones. Very bad ones.”

“[…] inspiration is always augmented through improvisation, collaboration, serendipity, and plain, old, unglamorous Hard Work.”

“[…] in television there is only one way of doing that: have great characters who are interesting to watch as they solve problems onscreen.”

“What I just described was only one of a continuum of very interesting, ongoing, moments in which improvisation—coupled with a strong conceptual foundation of previously generated ideas—provided crucial watershed events for the series.”

This long piece is packed with insights that can’t all be applied to our experiences on this comic, if only because the collaborative aspect is much more restricted here. So there is something for everyone to pick and choose from among his ideas.

But the idea of having a long-term plan and, at the same time, leaving room for short-term improvisation is something we apply in all our story lines. Here are a few examples:

Blascovitch was supposed to die much later on in the series, but we found this new timing quite appropriate. He’d made his major contributions, and his death opened the door for changes in the dynamics between Valasquez, Markham and Wood.

In the story “Going All Out—Part II,” Valasquez was supposed to let Gypsie go after torturing her. We decided to have her escape instead, as it was a good demonstration of her strength of character.

Votan—or at least Travis—was also supposed to die much later on in the story arc, but here again, the details were fuzzy. By getting rid of him earlier—and mainly via Cesar, who was egged on by his wife—we opened the story up to new interrelationships, whose potential we can sense even if we don’t yet have a clear picture of all the coming ramifications.

Characters live through their choices

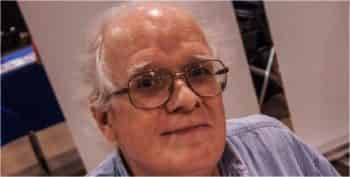

John Ostrander discusses the issue of writing stories, and posits what he calls Newton’s First Law of Plot. Here’s a long quote from this great piece.

“What is important is not what the character says (or anybody else says about them); it’s what they do. It’s what they choose to do. Their choices define them. […] How do we determine what a given character will do in any given situation? It depends on their motivation. It’s not simply what they want; it’s what they need. It’s not just what they desire; it‘s what they lust for. […] We want something that will drive a character to action and that’s not always easy. Newton’s First Law of Motion states that a body at rest will remain at rest unless an outside force acts upon it, and a body in motion at a constant velocity will remain in motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an outside force. That’s true in a narrative as well. Maybe we’ll call it Newton’s first law of plot.” (“John Ostrander’s Writing Class: Newton’s First Law of Plot,” http://www.comicmix.com, March 29, 2015).

This brings us to an observation made by Darren about James Bond: “Ian Fleming originally constructed James Bond as a one-dimensional cypher, not too far removed from the original version of Sherlock Holmes who appeared in the works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Characterisation was often inferred by the reader rather than explicitly articulated by the writer. A lot of what made Sean Connery or Roger Moore’s take on the character so fascinating existing as subtext rather than text.” (“Non-Review Review: Spectre,” https://them0vieblog.com, October 24, 2015). So, while Ian Flemming made his hero into a blank slate, his novels were still successful. This can be justified by Ostrander’s idea of motion, mentioned earlier.

One could argue that this option is valid only in action stories, but we see another facet of the idea of choice, which we’ve already mentioned: consequences. For instance, take a look at Vikram Murthi’s analysis of Don Draper: “[Don Draper]’s neither a murderer nor a psychopath, but he also doesn’t share the same motivations and desires with other antiheroes. He’s not on a quest for power or dominance, he doesn’t strive to destroy his enemies, and most importantly, he’s not beyond redemption. While Tony [Soprano] was the devil who lived next door and Walter [White] was the criminal mastermind disguised as your science teacher, Don is a socially sanctioned confidence man hiding his broken interior with a suit. He doesn’t exist on a good-bad continuum. He’s simply a man who wears many masks. […]Mad Men is one of the all-time great shows about self-destructive behavior and the toxic cycles someone falls into when they believe they don’t deserve anything better.” (“Don Draper is No Antihero,” http://www.avclub.com, March 30, 2015). Don is continually making choices—often bad ones—and a fair share of the TV series is built around his ability, or not, to come to terms with them. Therefore, the motion that Ostrander is talking about doesn’t necessarily only apply to superhuman actions.

Going beyond duality: The experience of Lost

Columnist Davin Faraci gave his analysis of comments made by Javier Grill–Marxauch about his writing for the TV series Lost. Faraci ends on this note: “Unfortunately the ways the show dealt with these topics—like the Manichean battle between good and evil—simply weren’t up to the level of what was happening in seasons one through three.”(“Walt Was Psychic: An Amazing Look at the True Development of LOST,” http://birthmoviesdeath.com, March 24, 2015). In our view, this is partly accurate, but the series’ greatest shortcoming was in the psychological development of the Man in Black. One episode uses flashbacks to try to show his motivations and his relationship with Jacob and his mother. It shows a man who really wants to leave the island, but whose dreams are crushed by his mother. Because of this, he kills her, and his brother seeks to destroy him. From a man who craves freedom, he evolves into a creature of destruction with only a single motivation. But his origin story showed a more nuanced person. And his brother, Jacob, wasn’t a compassionate character. In short, the series, rather than developing a more nuanced relationship between the two, adopted a classic Manichean duality, where the viewer cannot feel any compassion for one party. This was a missed opportunity for a much richer ending to this TV series that had otherwise taken so many risks during its run.

Concepts are good, but story is better

In his critique, Film Crit Hulk Smash provides a terse diagnostic of Amazing Spider-Man 2 (“Hulk’s Burning Questions for the Amazing Spider-Man 2,” birthmoviesdeath.com, May 6, 2014): “WHY DOES THIS CREATIVE TEAM KEEP FLIRTING WITH CONCEPTS AND THEN NOT ACTUALLY DEALING WITH THEM OR EXPLORING THEM? […] WHY DO WRITERS CONTINUALLY NOT UNDERSTAND THAT SCREENTIME ISN’T ABOUT POSITIONING THE LOGISTICS OF WHY PEOPLE DO WHATEVER, BUT ABOUT THE RELATIONSHIPS AND THE MEANING OF THOSE RELATIONSHIPS?” And there’s so much more quotable stuff in there.

Arthur Tebbel is just as harsh: “Stop teasing me on the Sinister Six if you can’t give me one compelling villain in this movie. Stop giving me the mystery of Peter Parker’s parents when you can neither give Aunt May enough space nor have Peter remember the death of his uncle.” (“Box Office Democracy: The Amazing Spider-Man 2, www.comicmix.com, May 5, 2014).

And to really drive it home, SouronsBane1 adds: “What’s even worse is the fact that there are a number of more minor subplots that come up out of nowhere, have valuable screen-time dedicated to setting them up…and then they ultimately end up going nowhere as well.” (“Why It Didn’t Work: The Amazing Spider-Man 2,”www.comicbookmovie.com, May 28, 2014.)

The idea here isn’t to belabour the point on this movie that certainly had its share of bad reviews, but to learn something and improve our own writing abilities. We often get the impression that writers and screenwriters want to stand out for ever-more-complex plots, when it takes a lot of effort to express a simple story. Simplicity doesn’t mean lack of complexity, but it should mean lack of complication. And when we’re polishing grand ideas, we tend to forget the small details that make a real difference. The question we should ask ourselves is: “Does this plot have too many improbabilities, too many gratuitous coincidences, that in the end the reader will more interested in pointing them out than in getting absorbed into the story?” The answer isn’t simple, but a little logic should be deployed in a story.

The narrative innovations of Star Wars

While our last entry may have seemed critical of the Star Wars saga, we can’t disregard its many technical innovations and narrative risk-taking. Keith Phipps (“Why Star Wars?,” thedissolve.com, November 14, 2014) gives a good example of these risks:

By opening with C-3PO and R2-D2, Star Wars thrusts viewers into its world and counts on them to be engaged enough to figure out what’s going on. Even if Star Wars’ title hadn’t been amended to add “Episode IV,” it would still feel like a story already in progress, complete with talk of a Galactic Senate, a never-seen Emperor, spice-smuggling (an homage to Frank Herbert’s Dune), and a past filled with Jedi. The action stops for the occasional explanation, but more goes unexplained.

And when you think about it, the characters are introduced gradually, in large expository scenes that allow each one to position him- or herself. It’s fair to wonder whether, in the current screenwriting climate, this approach would even be used if the episode were remade.

Are superheroes fascist?

Faraci revisits the oft-touted argument that superheroes are fascist: “Superheroes are essentially fascist because they use force to accomplish their goals, and their goals are almost always supporting and protecting the status quo.” (David Faraci, “Are Super-heros Fascist?” December 1, 2013, http://badassdigest.com.). The status quo is more than bearable if the superhero is a multi-millionaire, but then we may wonder whether the hero is acting for the benefit of others or to preserve his or her own social standing?

The latest Captain America, The Winter Soldier, offers a counter-argument to this opinion. The shield bearer doesn’t stop at defeating the bad guys’ plot, he also destroys his employer, Shield, which he feels has become too corrupt to pursue its mission. It should be noted that Cap’s altruism is his trademark.

What should we write: what the author wants or what the reader wants?

We came across this analysis about “Man of Steel”:

“Some might look at that scene and ask, “What else could Superman have done?” Others might offer alternative endings to the scene. It’s not a useful conversation. It’s the usual, “Who would win in a fight?” The answer is always that the outcome is determined by the writer, and the story bends to fit that outcome. Superman killed Zod not because there was no other choice, but because the people conceiving the story wanted Superman to kill Zod. (By a majority of two-to-one, according to recent reports.)” (Andrew Wheeler, “Choice and the Moral Universe of Man of Steel’ [opinion],” June 21, 2013, http://comicsalliance.com.)

Several streams of thought collide here. On the one hand, some authors want a kind of integrity for their work, their characters and the story they have been carrying inside them, sometimes for years. Other, more practical, writers just want to be read, and in that case, it may be tempting to turn to tried-and-tested formulas to grab the audience’s attention. The conventional opinion has been that integrity should win over the forces espousing a certain artlessness. However, we believe it’s not the recipe that leads to success but the right proportion of ingredients. And that’s where an author can stand out and give his or her work a personal touch.