Writing

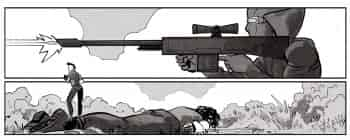

Looking for the perfect way to kill off a character

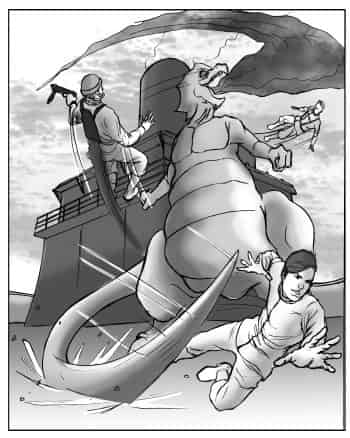

Let’s take another look at Hicham’s death: I thought long and hard about the perfect scenario for his death. I knew Akbar would be the killer but I wasn’t sure how he would do it: Strangulation? Stabbing? Finally I decided a long-distance gunshot should kill him. This fit in nicely with Akbar’s cold and determined nature.

Writing process

We really admire Ellroy’s outspokenness, which sometimes gives us pearls like this one: “It’s disingenuous when writers say that they have no control over their characters, that they have a life of their own. Here’s what happens: you create the characters rigorously, and make clear choices about their behavior. You reach junctures in your stories and are confronted with dramatic options. You choose one or the other.” (Nathaniel Rich. “Interviews: James Ellroy,” The Art of Fiction No. 201).

Naturally, not everyone has the same writing style. Christopher McQuarrie tells us about his: “We always start with an ending, so we always know where the story is going; knowing. However, never to stay married to it. I’ve stayed married to endings before and it’s been disastrous. You’ve got to let the story take its own course.” (“Christopher McQuarrie Gets Verbal on the Usual Suspects,” cinetropolis.net, April 13, 2014).

On a similar note, let’s look at this excerpt from and interview with Sam Esmail on the creation of the plot for the second season of Mr. Robot:

“Interviewer: Can we talk about Angela a little bit? Her scenes were probably my favorite this season — you have that emotional karaoke scene, but you also have that episode where she’s doing the hack that set my heart racing. Had you always envisioned this type of role for her?

Sam Esmail: No, no. This is the great thing about TV is that when you discover certain strengths in an actor you can then begin to exploit them in really fun ways. I was shooting the season finale last year, the shoe store scene, and she says that line about the Prada. I’m watching this scene in the edit bay, and I don’t know, is she enjoying this or is she embarrassed, is she shameful about how she treated this poor guy or is she actually getting off on it? I actually thought, Portia has this weird, uncanny ability to be right there in the middle. She was the one that spoke to me and guided what the journey of her character was gonna be this season.” (Jen Chaney , Gazelle Emami and Matt Zoller Seitz. “Mr. Robot Creator Sam Esmail on How He Handles Criticism of the Show,” www.vulture.com, September 28, 2016).

We can think about how actors bring a skill set to a project that the writer couldn’t have anticipated during the original creation. During any creative process, we make little choices that we hadn’t predicted 10 pages or 10 stories earlier. It’s these little alterations that open up a wide range of new options for the author. Therein lies the flexibility that seems to guide an author.

What to write when everything’s been said? (

We like reading about other writers’ creative processes. We came across this interview with Sam Esmail, the multitalented person behind the Mr. Robot TV series, in which he discusses his primary concern in plot development: “And I was hamstrung in the first season because I was like, well, this is really only the first act, I need this thing to happen, I need this plot, whatever, the hack thing to happen. Because for me, plot is always an excuse to explore characters. ‘Cause who cares? The plot is the same plot that we see in basically every movie and TV show. But how we tell that story, what choices these characters could make …” (Jen Chaney , Gazelle Emami and Matt Zoller Seitz. “Mr. Robot Creator Sam Esmail on How He Handles Criticism of the Show,” www.vulture.com, September 28, 2016).

This is especially interesting to read when paired with the following quote from Christopher McQuarrie, who’s had a long career as a screenwriter for the movies and, more recently, as a director. Here he talks about writing The Usual Suspects: “There’s a part of us that wants to see the bad guy get away, that wants to see this guy outsmart authority, and beat the system. That to me is when a movie is really good: when no one is an idiot. Early on in the development of the Suspects script someone asked me why Kujan was chasing this guy Keaton. What does he care? Did Keaton kill his partner? No, he’s just passionate about his job. You don’t have to be Vincent Van Gogh to be passionate about what you do […] So many movies use revenge as motivation for characters. But I think that, unless you’re analyzing the mindset itself, it’s a bad motivation.” (“Christopher McQuarrie Gets Verbal on The Usual Suspects,” cinetropolis.net, April 13, 2014).

These two quotes may come from different places, but together, they say something about how you can’t always approach characterization directly. Otherwise, verbalizing a character’s choices can take away the spontaneity and contradictions that are inherent to human behaviour.

Taking it slow

While rereading one of Film Crit Hulk’s comments on episode 7 of the Star Wars series (Force Awakeness) (Film Crit Hulk Smash: “STAR WARS: THE FORCE ALLUDED TO…” birthmoviesdeath.com, June 28, 2016), we highlighted several passages, but these two really stuck with us:

“HULK FEELS LIKE HULK NEEDS TO SHOUT FROM THE ROOFTOPS. THERE IS PLENTY OF “DANGER” IN THE MOVIE, BUT THERE ISN’T ANY DRAMA OR DOUBT OR ACTUAL CONFLICT BEING PLAYED. AND HE CONSTANTLY FINDS HIMSELF IN SITUATION WHERE CHARACTERS HAVE TO WASTE TIME EXPLAINING WHAT JUST HAPPENED. BUT J.J. OBVIOUSLY REALIZES THIS INFORMATION SUCKS TO DELIVER SO HE TRIES TO ZAP THROUGH EVERYTHING WITH PERSONALITY AND PIZZAZ BEFORE DISTRACTING US WITH A NEW SHINY ELEMENT OF “DANGER,” WHICH DOESN’T ESCALATE, BUT JUST CREATES THE LAW OF DIMINISHING RETURNS. AND IT SEEMS LIKE J.J. IS EVEN AWARE THAT THIS DOESN’T “WORK” SO HE’S TRYING TO STREAMLINE AND MOVE AND FIX AS QUICK AS POSSIBLE.

[…]

WAS EXPOSITION SIMPLY NOT “DELIGHTFUL” ENOUGH? DOES EXPOSITION STOP THEM FROM RUSHING THROUGH EVERY SCENE TO GET TO THE DESIRED EFFECT? HULK SORRY, BUT EFFECTIVE EXPOSITION IS ACTUALLY REALLY IMPORTANT TO MOVIES (EVERYONE MAKES FUN OF INCEPTION, BUT THE FIRST HALF OF THAT MOVIE IS WHAT ALLOWS THE SECOND HALF TO WORK WITHOUT STOPPING TO EXPLAIN ANYTHING). SO IT’S TIME TO TALK ABOUT ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SCENES IN THE ORIGINAL STAR WARS.

THAT WOULD BE THE CONFERENCE ROOM SCENE. YOU KNOW THE ONE:

THIS SCENE, LIKE MANY OTHER GREAT EXPOSITION SCENES, WORKS BY UNDERSTANDING THAT, YES, EXPOSITION IS BORING IN AND OF ITSELF. BUT THAT’S WHY YOU BEND OVER BACKWARDS TO FIND WAYS TO MAKE IT INTERESTING/FULL OF CONFLICT. LIKE THE FAMOUS SNAKE PLISSKEN NEGOTIATION, THERE’S STAKES AND AN ART OF GROUNDING IT IN REAL CHUTZPAH. AND IN THIS FAMOUS SCENE, THERE’S THAT AWESOME FRAMING CHOICE WITH TWO PEOPLE ARGUING SO IT FEELS LIKE JUST AN INTENSE CONVERSATION BETWEEN THEM. THEN THE SWEEPING WAY GRAND MOFF TARKIN COMES INTO THE ROOM. AND THEN OF COURSE, THERE’S THE WAY VADER TAKES CHARGE OF THE SITUATION (WITH A GUY WHO FEARLESSLY TAKES HIM ON BY THE WAY, AN IMPORTANT HUMANIZING FEATURE FOR VADER) AND THEN ISSUES ONE OF THE MOST ICONIC LINES OF THE ENTIRE SERIES. ALL IN ALL, THE SCENE IS FLIPPING FANTASTIC.”

And that’s very true: the conference room scene worked wonderfully; however, you have to be careful not to artificially create those tensions just to make a scene more dynamic.

The creative process is a conversation

We all know that, today, almost every story has already been told. And art doesn’t arise out of nothingness. Writers, painters, directors and other artists create their work in communion with their environment. So we admire a director like Quentin Tarantino who’s not afraid to announce his influences.

Andrew Wheeler says it well: “Star Wars was inspired by Flash Gordon. A Song of Ice and Fire owes a debt to The Lord of the Rings. Harry Potter offers an answer to The Chronicles of Narnia. Breaking Bad takes its lead from The Godfather. Jason Bourne took shape against James Bond.

“Art exists in conversation with that which came before it, and that’s as true in comics as in any other narrative form. […]Everyone who tells stories or creates art is a critical thinker, responding to ideas with ideas of their own. There aren’t just two types of people. Makers are critics.” (“‘If You Don’t Like It, Make Your Own’ Is a Terrible Argument, but a Great Idea,” http://comicsalliance.com, September 2, 2015).

So we don’t have any hang-ups about presenting what has inspired sections of our stories, or even whole stories.

What’s troubling though is unintentional borrowing. It is possible that certain parts of a given film or novel made an impression, without us remembering it explicitly. Kate Willaert talks about this phenomenon: “Being such a huge Jack Kirby fan, is it possible Alan Moore read this story at some point and simply forgot about it? Or for that matter, could The Architects Of Fear writer Meyer Dolinksy have read it?

“A creator forgetting they encountered an idea elsewhere isn’t an uncommon phenomenon, especially in the music world. Paul McCartney has a famous story about how while writing “Yesterday,” he became paranoid that he might’ve accidentally nicked it from somewhere. After playing it for just about everyone he knew and no one saying they recognized it, he felt confident that it was completely original.” (“Did Watchmen Steal From the Outer Limits, Or From Jack Kirby?” http://www.comicsbeat.com, August 10, 2015).

In a world like ours, we really have to stop looking for plagiarism. We should admit our influences and honour them. The word plagiarism should only be applied to outright copying, and not to borrowing. Otherwise, we could never again see any of Tarantino’s movies.

The temptation to be pompous—Part II

Joss Whedon said that emotions were the main thing at stake in his movie Avengers: Age of Ultron, and that his source of inspiration was Godfather II. Joss Whedon’s track record is far too impressive for us to be giving him advice. But, if emotion is the main thread, then there was already a goldmine available within the story line itself, in the issue of descendants. Black Widow can’t have children because of her training. Neither can Bruce Banner, but for different reasons. Ultron considers Tony Stark his father, and Vision is in a way, his son. The Avengers stories that inspired the movie (Ultron Unlimited, Avengers vol. 3, issues 19-22) showed Ultron trying to collect a variety of mental schemas to recreate an artificial lifeform, where different points of view could be shared. In sum, we feel the film could have gone into greater depth of feeling instead raising the bar with the physical challenges needing to be solved (saving the world, again).

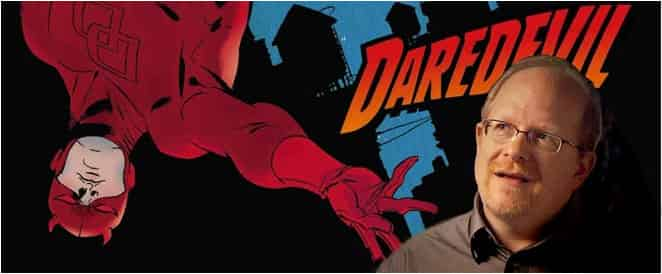

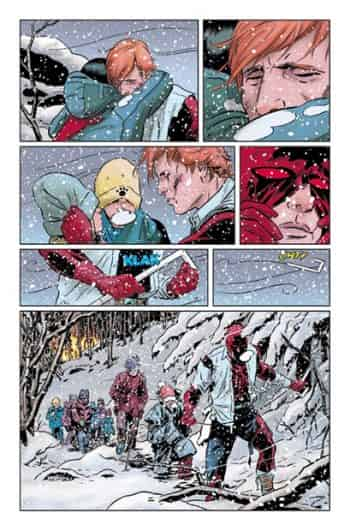

The summit of Mark Waid’s art

Our admiration for Issue 7 of the Daredevil series, written by Mark Waid, is boundless. And Dylan Routledge feels the same: “I’d also love to give a special shout out to issue 7 that pops up in the second volume of Waid’s Daredevil run as it is simply not only one of the best single issue of his run, but potentially one of the best Daredevil issues ever AND one of the best single issues to have been published in the last five years.” Dylan Routledge, “The Weekly Challenge: Mark Waid,” http://www.comicbookdaily.com, October 12, 2015).

We would describe this story as Daredevil vs. the snowstorm. We consider it the peak of an orientation taken by a few writers to bring superheroes back down to human scale, in terms of the trials they face. This doesn’t mean that these challenges can’t be life-or-death, but they don’t need to have intergalactic implications.

For this post, we did some research to find reviews of Issue 7. Christine Hanefalk uses the word charm to describe it and adds, “Amazingly, the story never goes into too sweet territory.” (“Review of Daredevil #7,” http://www.theothermurdockpapers.com, December 22, 2011). Waid plays with clichés without ever stumbling. He draws from the character’s personality. “Mark Waid takes established elements, like the difficulty Daredevil’s radar sense has with a snow storm, and uses them to create a daunting set of obstacles for the characters to survive.” (Wed, “Review of Daredevil #7,” http://www.comicbookresources.com, December 21, 2011).

We naturally also found negative reviews—and even some very negative ones. We decided not to cite them here, not to censor an opinion—because interested readers can find them easily—and not to glorify the author either. We’re not doing a literary analysis of all of Waid’s work on Daredevil. Our goal here was just to express our admiration for him and for this issue, and the story developed in it.

The temptation to be pompous—Part I

In superhero films or their comic book equivalents, there’s always a temptation to outdo the previous chapter. Russ Burlingame sums it up like this: “Each new film has to be bigger and bigger… [so] that the Marvel Studios films are spectacular adventures, but that they ultimately are so filled with spectacle that there isn’t a ton of room for story.” (“Is Captain America: The Winter Soldier the Best Marvel Movie Yet?”, http://comicbook.com, April 6, 2014). Along the same lines, Joe Casey says these huge-scale events leave increasingly less substance for readers—“less and less thematic resonance” (“CR Sunday Interview: Joe Casey,” http://www.comicsreporter.com, February 16, 2014). Mike Gold also points out the redundancy problem, when the consequences of these events are quickly fixed in the ensuing stories: “over the past 30 years the DC fans have learned one and only one thing: we cannot trust DC to sustain a thought.” (“What Goes Around Inevitably Comes Around,” www.comicmix.com, September 10, 2014).

SauronsBANE elaborates on this theme, offering a few suggestions. “Of course, a proper sequel really should improve upon the 1st film… by raising the stakes. Unfortunately, I believe too many filmmakers get caught up in trying to raise the scale. See the difference?

On one hand, you can have an effective sequel that successfully manages to make things matter more. There’s more at risk if the hero should fail. Indeed, by raising the stakes, the natural result is that drama, conflict, and tension all become heightened as well. Of course, that naturally leads to a more entertaining, emotionally resonant film that’s easy to get invested in. This is basic filmmaking 101.

“But on the other hand, by only raising the scale of things in a sequel, it just leads to a series of movies that steadily progress from something as superficial as city-wide threats, to nationwide threats, to planet-wide threats, and possibly even universal threats. This may seem like a legitimate way of doing things in film, but I can pretty much guarantee that there is no better way to ensure that a series of movies become as boring, repetitive, cliché, and unoriginal as possible.” (“Top 3 Worst Hollywood Trends,” http://www.comicbookmovie.com, July 8, 2015).

In our opinion, Cap’s latest film, Captain America: Civil War, provides stakes that have depth rather than just size. At the film’s end, we see a superheroes clash, but not to save the world: it’s because one of the protagonists wants to avenge the death of his loved ones.

Without stretching the comparison too far, after the confrontation that happened in the Arctic in the Apatrides story, which featured a lot of players and a larger-scale deployment, we shifted back to more circumscribed stories. We did this for two reasons: To keep upping the ante with ever-larger stories is not viable, in that the element of surprise is lost for the reader. And, also, these events have to be led up to. You can’t just pull them out of hat.

Tips for writing women

Writing for a female character can be a stumbling block for some male writers. But we recently found inspiration in this tip from Janelle Asselin (“Great Writing Advice: Learn To Write Women Like They’re Human Beings,” http://comicsalliance.com, March 5, 2015). Her advice was a revelation, even though it’s surprisingly simple:

“Have enough women in the story that they can talk to each other. The lack of women talking to each other is the most frequent criticism I have of writers writing women (especially male writers). Pay attention to the fact that women DO talk to each other. Create opportunity for women characters to talk to each other. Check to see if you-as-writer are missing chances to have women talk to and interact with each other.”

This comment made us rethink the future of some characters, especially Liane. She was initially going to die after a suicide attempt, but our decision to replace Benson with a female team leader created an opportunity to deepen the dynamics between women.