James Bond

Characters live through their choices

John Ostrander discusses the issue of writing stories, and posits what he calls Newton’s First Law of Plot. Here’s a long quote from this great piece.

“What is important is not what the character says (or anybody else says about them); it’s what they do. It’s what they choose to do. Their choices define them. […] How do we determine what a given character will do in any given situation? It depends on their motivation. It’s not simply what they want; it’s what they need. It’s not just what they desire; it‘s what they lust for. […] We want something that will drive a character to action and that’s not always easy. Newton’s First Law of Motion states that a body at rest will remain at rest unless an outside force acts upon it, and a body in motion at a constant velocity will remain in motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an outside force. That’s true in a narrative as well. Maybe we’ll call it Newton’s first law of plot.” (“John Ostrander’s Writing Class: Newton’s First Law of Plot,” http://www.comicmix.com, March 29, 2015).

This brings us to an observation made by Darren about James Bond: “Ian Fleming originally constructed James Bond as a one-dimensional cypher, not too far removed from the original version of Sherlock Holmes who appeared in the works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Characterisation was often inferred by the reader rather than explicitly articulated by the writer. A lot of what made Sean Connery or Roger Moore’s take on the character so fascinating existing as subtext rather than text.” (“Non-Review Review: Spectre,” https://them0vieblog.com, October 24, 2015). So, while Ian Flemming made his hero into a blank slate, his novels were still successful. This can be justified by Ostrander’s idea of motion, mentioned earlier.

One could argue that this option is valid only in action stories, but we see another facet of the idea of choice, which we’ve already mentioned: consequences. For instance, take a look at Vikram Murthi’s analysis of Don Draper: “[Don Draper]’s neither a murderer nor a psychopath, but he also doesn’t share the same motivations and desires with other antiheroes. He’s not on a quest for power or dominance, he doesn’t strive to destroy his enemies, and most importantly, he’s not beyond redemption. While Tony [Soprano] was the devil who lived next door and Walter [White] was the criminal mastermind disguised as your science teacher, Don is a socially sanctioned confidence man hiding his broken interior with a suit. He doesn’t exist on a good-bad continuum. He’s simply a man who wears many masks. […]Mad Men is one of the all-time great shows about self-destructive behavior and the toxic cycles someone falls into when they believe they don’t deserve anything better.” (“Don Draper is No Antihero,” http://www.avclub.com, March 30, 2015). Don is continually making choices—often bad ones—and a fair share of the TV series is built around his ability, or not, to come to terms with them. Therefore, the motion that Ostrander is talking about doesn’t necessarily only apply to superhuman actions.

If it ain’t broke…

We happened upon an interview with Michael G. Wilson, who explains the success of the Bond franchise. One of the points he makes is that the team tried to reinvent the myth before it could become too hackneyed (Edward Cross, “Skyfall Exclusive: An Interview with Producer Michael G. Wilson,” www.comicbookmovie.com, February 13, 2013). Similarly, Harvey Weinstein admits he made some mistakes in promoting the movie The Master, which resulted in it not reaching its audience (Sean O’Connell, “Harvey Weinstein Admits He Mis-Marketed The Master,” www.cinemablend.com, January 29, 2013). These two statements in our opinion demonstrate a kind of humility: admitting our errors allows us to learn something that can be applied to similar situations in the future.

Focussing on the characters

We’ve already discussed Mark Waid at length, along with his writing techniques focusing on character rather than on large and complex machinations. We feel this is a product of our time. In his analysis of Skyfall, FamousMonster states, “The screenplay, written by John Logan, Neal Purvis, and Robert Wade, is a swaggering return to classic Bond, with an intense focus on characterization and action, as opposed to some of the more recent Bond films, which seem primarily concerned with car chases and stunt sequences” (Movie Review: Skyfall, FamousMonster, http://www.geeksofdoom.com, November 9, 2012).

A few months before, Mendes spoke similarly about the movie: “Yes, they do have a history […]. It’s much more personal story than your traditional ‘I’ve got a nuclear device and I’m going to blow up the world, Mr. Bond.’ […] You know, just making it bigger is not going to make it any more scary” (“We’ve Been Expecting You Mr. Bond,” Dan Jolin, Empire, n° 280, October 2012, p. 94-103.).

Without even being aware of it, Joss Whedon may possibly go in the same direction for his Avengers 2. “On the tone of the film, he [Whedon] said that The Avengers 2 would go deeper instead of bigger. Honestly after a huge battle like the one we saw in the first film, it be nice to get a more personal story and take a step back from the big hefty action. Apparently he wants to go so deep and personal that it will be painful.” (“Joss Whedon Talks ‘Avengers 2′ Script, ‘S.H.I.E.L.D.’ TV Show & Marvel Films,” eelyajekiM, www.geeksofdoom.com, January 11, 2013).

Inconsistencies and story

We’ve already mentioned the inconsistencies can be deliberately left in a scene to amplify mystery or even realism, since after all, we don’t always behave logically. But other inconsistencies may not necessarily be voluntary. In his analysis of the character of Goldfinger in the movie of the same name, Darren notes the following: “Like a lot of Goldfinger’s actions over the course of the film, one wonders why he didn’t just ask Oddjob to remove the gold from the car before he crushed it. After all, Solo was dead and unlikely to complain. Perhaps, like the rest of Goldfinger’s somewhat contradictory actions, it just allows the man to show off, feeding into his desire for attention and his demands for respect. Perhaps he just gets a giddy thrill at the idea that his gold blocks have mingled with a mushed-up gangster” (A View to a Bond Baddie: Auric Goldfinger, Darren, them0vieblog.com, October 4, 2012).

The French-language Wikipedia page on the movie Once Upon a Time in the West brings up similar questions about an injury suffered by Charles Bronson’s character. One of the theories is that the script wasn’t well understood during the editing process.

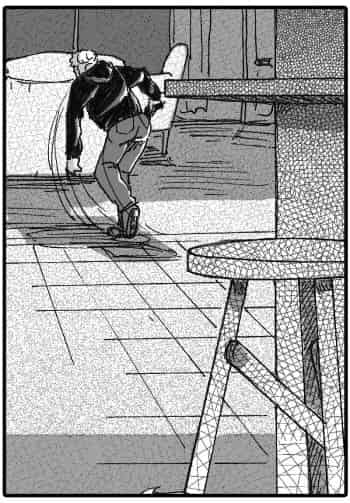

In the box below, taken from our story ” A Man to Kill,” we see Chad getting up but he has his back to the action when he should have been facing it. This is one inconsistency that got past us, despite several production stages.

Ideas floating in the air– Part III

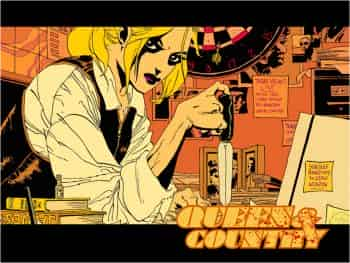

We start our stories off by showing the faces and names of the main characters, to help the readers identify the actors in that particular story, but also because the look of the characters may change slightly depending on who is illustrating it. The other benefit of this approach is that it saves us from having to use up panels to present the characters again, allowing us to showcase more direct conversation between them. Recently, while reading a Queen & Country comic book by Greg Rucka (developed by him in the late 2000s), we noticed that it used a similar approach.

Now, let’s talk about the last James Bond film, where the spy’s weapon won’t work if the fingerprints on the hand holding it don’t match the owner’s. We wrote something like this in Divide to Conquer a long time before we saw Skyfall. In our story Grant uses a similar device for his weapon.

What we’re trying to show here is that ideas may be used by several writers without necessarily having been copied. Sometimes this happens by accident, simply because ideas float around in the air at certain times, waiting to emerge. Two writers may have tuned into them at separate times without being aware of it.

Ideas floating in the air– Part I

Today, it’s hard to create something that’s fundamentally original. Stanley Kubrick is said to have told Jack Nicholson, “You know, in a way every scene has already been done in film. Our job is simply to do them a little better” (Kubrick, Michel Ciment, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1999, p. 297). Now that we all have easy access to the accumulated knowledge of centuries, it’s hard to pretend that knowledge doesn’t exist.

In an interview, Sam Mendes said Nolan’s Dark Knight was a revelation in his approach to the latest James Bond (“The Dark Knight Skyfall: New Bond Director Drew Inspiration from Nolan’s Batman,” Russ Burlingame, October 19, 2012). But at the same time, Darren, in his analysis, shows that Nolan’s Batman owes a great debt to the Bond franchise: “What Bond Learned from Batman: The Dark Knight & Skyfall […]” (Darren, them0vieblog.com, October 26, 2012). He adds that these dynamics of mutual influence should not be avoided, but we must learn to draw the right lessons from them.

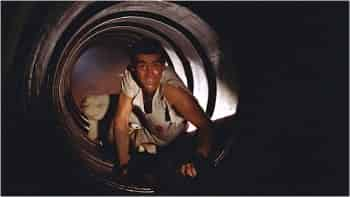

References in Plain View

We are constantly bombarded by stories (TV, movies, newspapers, books, etc.). Unconsciously or even deliberately, we borrow ideas we’ve seen elsewhere and insert them into our stories. So in the story, “The Test,” we reuse the tunnel that heats up and the electric grate from Doctor No. Surely many people recognized it. We didn’t try to hide that we were borrowing it. In fact, Jason explicitly refers to it in one of his one-liners.

The Role of the Villain

We’ve mentioned that we want to give our characters a complex personality. And you know what they say: the better the bad guy, the better the story. In our opinion, villain Oroshimaru gives Naruto a whole new dimension. His nearly metaphysical ambition to master all forms of combat is a welcome alternative to the usual ambition of world domination. “Goldfinger” (the movie) remains one of the best Bond films because the confrontation between hero and villain is not only physical but also psychological. In the ensemble film “Syriana,” Christopher Plummer’s Dean Whiting only makes a few appearances but each time, his presence electrifies the scene. The same goes for David Strathairn’s role (Bourne Ultimatum), which, thanks to the work co-director Noah Vosen, is imbued with the strength of conviction. This villain doesn’t wake up in the morning looking forward to eating babies. Just like the good guys, he just wants to see his businesses succeed. We’ll come back to this topic later.

Being confortable with shades of grey

In his preface to the works of Ian Flemming, Francis Lacassin criticized the author of the James Bond stories for having created such black-and-white villains—bad guys that the police feel compelled to shoot on sight the first time they are seen in public because they are just so ugly, ridiculous or flagrantly tasteless. But some heroes can be ugly, just like some villains can be attractive. The same goes for their personalities: heroes as much as villains can display some flaws (like cowardice, for example). Our goal isn’t simply to turn all of the clichés on their heads, but rather, to have characters that offer a wide range of dramatic motivations, rather than just reactions that too often seem contrived.