Frank Miller

Collaboration between writers and illustrators

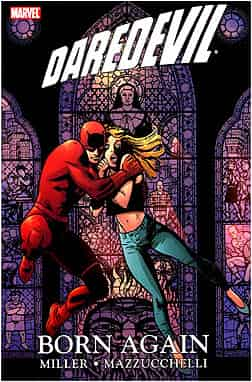

We have already spoken of the symbiosis that exists between words and illustration, but the relationship can sometimes be even more profound. Take, for example, the collaboration between Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli for the Daredevil series in the 1980s. Nadel says, “Very simply, the story follows Matt Murdoch/Daredevil as his life is dismantled by his nemesis, The Kingpin. He loses faith in himself and the world, then regains it. Miller conceived the story and then he and Mazzucchelli collaborated very closely, as described by the artist in his unexpectedly candid and moving introduction: ‘This is why we chose not to separate the credits into writer and artist; because although technically I did no scripting and Frank did no drawing, I was contributing ideas for plot, characterization, and storytelling (such as the succession of title pages charting Matt’s descent), while Frank was describing the contents of each panel in his scripts’ ” (“Some Thoughts on David Mazzucchelli’s Daredevil: Born Again Artist’s Edition,” Dan Nadel, www.tcj.com, August 27, 2012).

To illustrate, when Michel Lamontagne suggested that we write a story from the point of view of the villains, we found the concept interesting. This resulted in “Blitzkrieg.” This story puts a face to some of the characters who often remain anonymous, and shows some of the human repercussions of the Black Orchestra’s attacks.

Which tone to use?

Corey Schroeder reminds us that “Fast-forward to the 90s and you’ve got a new kind of Batman. Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns have reinvented superheroes as real people with real flaws in the midst of stories that treat the audience’s intellect with maturity” (“Are Superhero Comics Too Serious,” www.comicvine.com, September 14, 2011). Chris Sims goes even further: “The imitators learned the wrong lessons, and instead of creating stories that treated their subject matter with intelligence and craft, which is a difficult matter requiring a great deal of skill, the knock-offs tried to recapture the things that were easy, like cussin’ and violence. They were exactly the same kind of escapist power fantasy that they were pretending to rise above, just wrapped up in cheap, meaningless exploitation and sold to the audience as something that wasn’t for little kids — which in itself is the most immature, teenage motivation something can possibly have” (“What’s Up with the 90s?” www.comicsalliance.com, July 27, 2012).

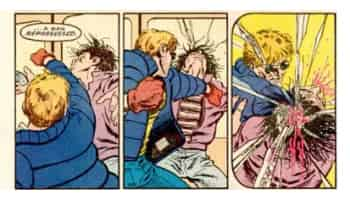

This may explain why some people wonder if superhero stories have become too violent (“Sex & Violence,” www.comicbookdaily.com, December 9, 2011). In our opinion, violence isn’t the real problem. In the 90s, Frank Miller’s Daredevil stories included some very graphic representations of violence. But they fit the mood. Our main reproach would be the lack of perspective about that violence. If we take the TV series 24, Jack Bauer tortured criminals but we don’t recall any innocent characters being tortured. We feel more uneasy about that situation than about the torture itself.

Comics and Movie – Inter-Connections Between Two Art Forms

Anthony Falcone had a great way of saying that comics are an inexpensive form of entertainment to produce: “comics are sort of book-movies” (“Why I Like Comic Books,” www.comicbookdaily.com, January 31, 2012). It’s true that comics are not restricted by budgetary constraints that might limit the number of characters or the location. And the author can use any type of special effect—even the most outrageous—without it costing an arm and a leg. Just remember that Rodriguez said that Frank Miller’s Sin City comic was more than a source of inspiration for the film, it was the storyboard for its development.

Now that superhero movies have a choice standing, they don’t seem to draw their inspiration only from the characters but also from the narrative styles of comics. In a critique of The Dark Knight Rises, J. Calab Mazzocco said, “Intentionally or not, The Dark Knight Rises also seemed to mimic one aspect of reading superhero comics, serial storytelling. I occasionally found myself wondering how all the callbacks to the previous films might sit with someone who never saw those, or only saw one of them but not the other” (“ComicsAlliance Staff Reactions to The Dark Knigth Rises,” www.comicsalliance.com, July 23, 2012).

Writing and Political Opinion (Part II)

Here are the words of a commentator on Frank Miller’s criticisms of the Occupy Movement: “I always separate the artist from the art; if I distanced myself from one of my heroes just because they said something I don’t agree with, I would barely have any heroes at all. It just bothers me to see Miller thumbing his nose rather abrasively at the Occupy Wall Street protesters instead of offering up any constructive criticism or intelligent insights” (“Frank Miller Rages Against The Occupy Wall Street Movement,” www.geeksofdoom.com, November 17, 2011).

We close this discussion with the view of James Ellroy, who says that Americans don’t give a rat’s ass about their writers’ political opinions (James Ellory, « Le temps des moutons », from Petite mécanique). This is an attitude we feel should be espoused by more people, regardless of nationality.

Writing and Political Opinion (Part I)

The release of the last Batman (The Dark Knight Rises) triggered a fierce media debate about Christopher Nolan’s political intentions. Was his Batman defending against the values of conservatism? The hysteria reached its peak when the villain’s name, Bane, was associated with the name of a company founded by Mitt Romney (Baine Capital). Chuck Dixon, the co-creator of Bane, had to make a public statement to declare his conservative beliefs (Jozef Siroka, « Batman ne porterait pas le carré rouge », www.lapresse.ca, July 24, 2012).

This is reminiscent of when Frank Miller harshly denounced the Occupy movement, a position that was then criticized (Brent Chittenden, “Oh Frank Miller… Creators and Politics,” November 17, 2011, www.comicbookdaily.com “Watchmen Writer Alan Moore Set to Occupy Comics After Spat With Frank Miller”, www.geeksofdoom, December 6th, 2011). However, as Sara Lima pointed out, V for Vendetta remains an excellent comic even if Alan Moore claims anarchy as the best form of government (“Do Politics in Comics Alienate Readers?” www.comicvine.com, October 6, 2011).

We feel that a work of art should never be crushed under the weight of political or social metaphor. Otherwise, the characters become unmoored from reality and their sole purpose is to be spokesmen for the author. Authors who want to deliver a strong social or political message should consider essay writing.