Writing

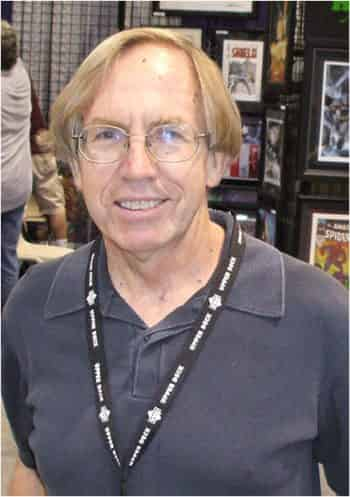

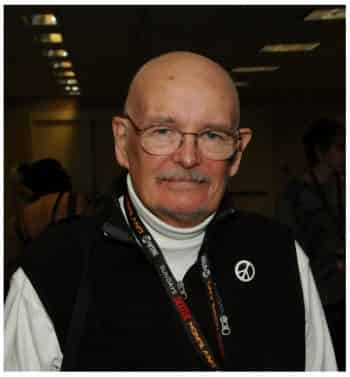

Mark Waid’s era in the Daredevil series

“To me, this run isn’t just the best ‘Daredevil’ run of all time (and that’s saying a lot)—it’s also one of the best comics, ever,” said Christine Hanefalk (“In Your Face Jam: Thanks For Making Me Cry, Daredevil, “», http://www.comicbookresources.com, September 2, 2015). We wish we’d said it first. We’ve repeatedly praised Mark Waid’s writing style. He’s an author we discovered with the Daredevil series, and we still believe he was in perfect symbiosis with his subject, creating one of the most organic stories, one that avoided tons of typical comic book pitfalls.

To fully understand the life that Waid breathed into this character, we have to remember the basic material he had to work with: “For years, Daredevil had been one of Marvel’s grimmest comics. Recent years had seen Daredevil outed as Matt Murdock at the hands of the Kingpin, loved ones murdered or driven insane by various villains, a stint in prison, and even a brief possession by a demon. When Mark Waid and artist Paolo Rivera took over Daredevil in 2011, many wondered how the two creators would destroy Murdock’s life next. The answer: they’d make Daredevil happy.

“The creator’s Daredevil run marked a return to the fun, swashbuckling superhero adventures not seen in a Daredevil book since the Silver Age. Not only did Daredevil beat gangsters and supervillains without losing loved ones or suffering personal tragedy in the process, he did it with a smile, pursuing life with a newfound optimism and bravado. For months, Daredevil readers waited for the other shoe to drop, because this was a Daredevil series and Matt Murdock could only experience so much good in his life before the Kingpin showed up at his doorstep and beat him half to death. But the wins kept piling up for Daredevil and while Matt’s personal life was a mess, he wasn’t adding to his problems with his typical self-destructive behavior. For the first time in years, Daredevil was a “fun” comic, a relative rarity in a genre filled with serious and straightforward takes on superheroes.” (Christian Hoffer, “A Look Back at Waid and Samnee’s Daredevil and Its Importance to Modern Comics,” http://comicbook.com, September 12, 2015). Despite this shift, Christine Hanefalk recalls that Waid never claimed that Matt Murdock’s depression was resolved. It was always there, and the hero just had to learn to live with it instead of making it a focal point of the story. “Waid shows that superhero stories can still tell serious stories without being dark and brooding” (Dylan Routledge, “The Weekly Challenge: Mark Waid,” http://www.comicbookdaily.com, October 12, 2015).

Aside from this shift in the character (while still remaining fundamentally faithful to it), the concept used, the reconnection, the homage to the Silver Age, was done in a very modern way: “Waid himself also contributes to the nostalgic mood of Daredevil, particularly with his choice of focus and guest characters. As well as bringing back old foes like Stiltman or the Jester or the Spot, he makes a point to focus on characters and concepts that feel tied and rooted in the sixties. Hank Pym is a recurring guest star, with the “hip scientist” and ant motif that defined the character in his earliest appearances. Indeed, Pym provides a link to the classic Avengers universe, nostalgically observing how things have changed. It’s not like the old days of the Avengers where everyone’s a casual identicard call away.” (Darren, “Mark Waid, Chris Samnee, Paolo Rivera et al.’s Run on Daredevil (Vol. 3) (Review/Retrospective),” https://them0vieblog.com, April 24, 2014).

This approach wasn’t loved by everyone. No one can achieve universal approval. “Reading the book feels more like something from the early 1960s than something modernized…” Andrew Ardizzi, «Daredevil # 7», https://www.comicbookdaily.com, December 26, 2011).

As is surely clear, we don’t agree with this last comment. An homage to sixties’ style would have resulted in overwriting, it would have made the topic of the story clear and unambiguous. But Waid lets the story speak for itself, and lets readers interpret the characters’ motives for themselves. For us, this style of writing is something to learn from and is a constant source of inspiration.

The challenges of continuity

In a piece discussing Roy Thomas’ career, Alex Dueben said this about continuity: “Continuity just came naturally to me. If you’re trying to get readers to take your world seriously, it seems to me that you have to take your world seriously enough that you treat it like a real world.” (“Roy Thomas Talks Creating Avengers Villain Ultron and His 50 Years in Comics”, http://www.comicbookresources.com, April 24, 2015). It’s like we often say: it’s not because the subject matter is light that you shouldn’t take it seriously. But creating this kind of continuity involves patience to develop the universe’s long-term ramifications (See Emily S. Whitten, “Writing the Long Game,” http://www.comicmix.com, May 12, 2015). But in today’s world, who takes time to throw themselves fully into the creation of a complex system of interrelations?

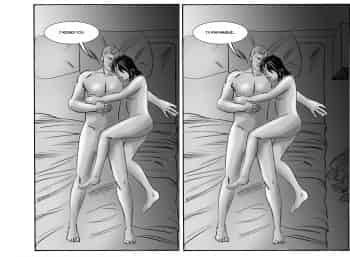

Women in control: Eva and Benson’s relationship—Part I

Chris Sims analyzes the role of the mistress and her interactions with the hero:

“And those are, in all honesty, the best case scenarios for a lot of love interests. Like everything in a comic book story, they exist to create drama, but superhero comics have historically had a very specific kind of drama in mind when it came to the fates of romantic partners, especially, overwhelmingly, women: They tend to wind up dead for the sake of a cheap thrill and setting up a villain. It’s a cliché so prominent that it’s become one of the best known tropes of the genre, and while that’s frustrating and detrimental on a lot of levels, it also has the very practical function of almost requiring new love interests to be introduced.” (“Ask Chris #260: Love, Exciting and New: On the Dramatics of Superhero Love Interests,” October 2, 2015).

Tasha Robinson says something along the same lines: “If she does accomplish something plot significant, is it primarily getting raped, beaten, or killed to motivate a male hero? Or deciding to have sex with / not have sex with / agreeing to date / deciding to break up with a male hero? Or nagging a male hero into growing up, or nagging him to stop being so heroic? Basically, does she only exist to service the male hero’s needs, development, or motivations?”(“We’re Losing All Our Strong Female Characters to Trinity Syndrome,” http://www.huffingtonpost.com, June 16, 2014).

In this area, Sims adds that “adding in a love interest is one of the best ways to reveal something about a character’s personal life—the type of thing that really makes you care about them beyond just getting into a punch-up with someone who’s trying to rob a bank while dressed as an egret or whatever—but it’s also a purely functional way to add in entirely new worlds of drama.”(“Ask Chris #260: Love, Exciting and New: On the Dramatics of Superhero Love Interests,” http://comicsalliance.com, October 2, 2015). Female characters are motivated by their own interests, which then makes it possible to reveal other characters’ feelings.

We don’t believe that creating strong female characters means putting them in the same positions as men, or, in other words, choosing to create a female instead of a male character and having her act the same way he would have. In the story “Home Sweet Home,” we are given a clue about where the lines are drawn in the relationship between Eva and Benson: It’s Benson who says that he missed her.

Forcing creativity, creating new conventions

Marc Alan Fishman points out that: “[Writers] can’t simply let their comic character live and die with the times. They must constantly be in a cycle or dramatic repartee with one another. They must converge on mighty battlegrounds. They must make odd alliances. They must recalibrate, reinvent, and redefine their very being every few months. The moment they stop, the attention is drawn elsewhere.” (“Wanted, Dead or Alive… Not Both,” www.comicmix.com, May 3, 2014). And in this vein: “The culture of superhero comics encourages repetition; Marvel and DC creators recycle tropes, story structures, and approaches to characterization. Inasmuch as readers approach these comics with certain expectations—to see the last-minute return of a believed-dead hero, the dissolution and reunion of a superteam, etc.—this isn’t necessarily a problem.” (Greg Hunter, “Batman: Death of the Family,” www.tcj.com, February 12, 2014.). And so, “idea generation is the true value of the end product. […] But if we chain the hands of our creative teams and force them to work within the confines of a limited universe, we’re removing the possibility of those teams then creating something truly memorable.” (Marc Alan Fishman, “Captain America, Thor, Changes, Stunts…,” www.comicmix.com, June 26, 2014). Thus the problem isn’t recycling concepts but developing them poorly. “You can figure out the rest. It was mind blowing to see how fandom had embraced Bucky, which more than anything, had to do with the magnificent story that Ed Brubaker was writing.” In a universe without the constraints of life or death, it’s execution that makes concepts—even recycled ones—stand the test of time.

Long-term writing stings

According to Matt D. Wilson: “Certain generations of comics readers remember their favorite runs as especially long, and the comics of their youth being particularly focused and author-driven. But the truth is that long runs have always been pretty special and fairly rare. Now, maybe the short runs are getting shorter.” (“Perception Vs. Reality: ‘Long Writer Runs’ At Marvel & DC,” comicsalliance.com, January 23, 2014). Is this a problem? Ultimately, we want to read good stories. So if authors are not able to offer us any, it’s normal that an editor will want to replace them. But a replacement author will want to make a mark, and will often resort to high concepts to strike the imagination (Juliet Kahn, “Putting the Sidekick in The Suit: Black Captain America, Female Thor, and the Illusion of Progress,” comicsalliance.com, November 24, 2014). But these ploys will rarely grab us like the original, or have continuity with the essence of the character. The downside is that this leads to sudden changes in a character’s personality. But an author who has the luxury of being able to work on a title for many years can develop ideas much more patiently.

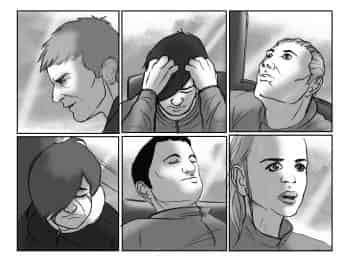

How far to go with character descriptions?

We came across this review of issue 7 of the Miracleman series that we found quite compelling:

Overall, the primary content of this issue is still quite excellent. Once again Cream is a confounding influence and the art does see a decline in quality, but the story is still very engaging and I’m honestly intrigued to see how Moran gets himself out of this mess. You see, Gargunza used the term “Abraxas” to turn Miracleman back into Moran. The word keeps him in his human state for an hour. He and Cream are then given a head start to run away from Miracledog before he is sicced on them. Cream hands Moran a gun before running off to be decapitated by Miracledog. The issue ends on a very human and very scared Moran confronted by the beast. I have no idea how he can save himself but I’m excited to find out. » (Michael Brown, “Marvel’s Miracleman # 7: Enter Chuck Austen,” comicbook.com, June 6, 2014)

There is a fine line to walk between giving a full character profile and maintaining an aura of mystery that leaves some interpretation to the reader. It’s a very fine line. Personally, we don’t like to over-explain the psychological choices of our characters, but we don’t want to neglect concrete actions either. The line is even harder to identify since we don’t always know where certain actions will lead. For example, at the start, Fabien didn’t want to sleep. But later, we saw that his former teammates were appearing in his nightmares. Then he started hearing voices. These events were layered one on top of the other without advance planning. However, they culminated in the story “Psychological Warfare.” While authors may be surprised by the twists and turns they themselves create, they should not leave the reader struggling to keep up.

Writing tips

We don’t want to offer writing tips—we still have too much to learn—but we love reading tips. Dennis O’Neil (“Dennis O’Neil: Mark Twain and the Seven Basic Plots,” www.comicmix.com, April 24, 2014) presents a pretty exhaustive list of tips. We like the last one: “Employ a simple, straightforward style.” No one is likely to give you an award for such a style but at least it will have the advantage of being in synch with your characters’ level of speech.

Can a hero fall in love?

In an analysis of the Christopher Nolan’s Dark Night trilogy, Slimybug arrives at this conclusion: “Many superhero films, including the first two films in this series, are about facing responsibility and obligations to others. The Dark Knight Rises is unique as a film in that it is about hero needing to love himself” (Slimybug, “The Themes and Meanings of THE DARK KNIGHT Trilogy,” www.comicbookmovie.com, January 14, 2014).

For Chris Sims, this may seem like a risky bet, narratively speaking: “But the thing is, as much as they don’t work from a romantic perspective, which is the nature of dramatic tension, they don’t really work from a storytelling perspective, either.” And the female lovers will almost always be supporting characters, serving the hero, but not having any real existence (Chris Sims “Ask Chris #212: The Many Loves Of Batman,” www.comicsalliance.com, September 12, 2014).

In these circumstances, the whole balancing act of writing is to give the lover a genuine existence without his or her role being reduced to that of damsel in distress or sacrificial lamb. These are traps that can be avoided in a two-hour film, but they are harder to achieve in longer-lasting series.

Reacting to external events

Our admiration for Mark Waid knows no bounds. We like the analysis he gives his own work. In an interview, he said this sentence, which we find very important: “I love the new directions of your Marvel books. Both Bruce Banner and Matt Murdock have fresh “onwards and upwards” attitudes. They’re deciding to change, whereas most of the time superheroes are more reacting to external events.” Reacting to events. He gives an example:

I think you see very clearly in Daredevil that depression is inertia. What fuels depression is that sense of helplessness, that sense of not knowing what to do next, that image of sitting on a gargoyle in the rain on the rooftop, frozen by inaction. To me, Daredevil come to grips with that and is actively pushing past. I wrote a scene where he feels that paralysis that comes with depression and he pushes through it. He makes an active decision to move forward. Any movement is better than no movement at all. (“Interview: Mark Waid on the Inner Demons of Daredevil, Attitude Adjustment for the Hulk, and the Thrill of Digital Comics,” www.comicsbeat.com, February 10, 2014).

Similarly, Greg Rucka, in talking about his work on Batman and on the death of Sarah Essen, said that “this death has to mean something.” (Chris Sims, “Born in a World Of Tragedy: Greg Rucka Reflects on His Batman Work, Part One,” www.comicsalliance.com, September 17, 2014). And when we look at the title of the article this quote is taken from, we realize that characters can experience tragedies—events over which they have no control—but at the same time, these same events must have some significance.

Heroes must take their destiny in hand, and at the same time, can’t be indifferent to the tragedies they see around them. At the end of the story “Counteroffensive,” Benson and his team return to the Bunker. They had been close to twenty when they left, and now are just a half-dozen. Did they win or were they slaughtered? Jenny has lost her brother, Liane is traumatized by the brutality of combat, and Benson must bear the weight of his decisions. They need to think about and absorb the consequences of their actions and those of others. This reflection process must lead to the upcoming events. That’s how we see heroes controlling their destiny.

Filling gaps

In a previous post, we posited that writers shouldn’t leave readers in the lurch about secondary events, but in the same breath, we admitted that writers can’t always know what’s coming up, plot-wise. We think our webcomic allows us to fill in some of these gaps. First, because our universe is separated into four storylines, we can handle several subplots at the same time. Then, by approaching them from different time periods, these subplots achieve their own pace. And lastly, because some storylines are not published chronologically, we can adjust as we go along to fill any plot holes that may appear.

For example, we had established that Gypsie and Tucker hated each other. This animosity drove Gypsie to discover Travis’ secrets. But once Gypsie got the Bunker, there had to be a period of time where these characters were bumping into one another. We hadn’t anticipated that. So in September 2015, we finally published a story showing one of these encounters, allowing us to fill in a plot gap. Also, since were writing the story anyway, why not suggest that something else may have intervened in Tucker’s destiny…