Writing

The ramifications of our characters’ lives

Wherever possible we try to give our characters a social life. We want to give them a life that extends beyond the scope of the story they are in. For example we wanted Cesar to have a wife and kids. That way he doesn’t exist solely to interact with the other characters in the story; he also has a life outside it.

If it ain’t broke…

We happened upon an interview with Michael G. Wilson, who explains the success of the Bond franchise. One of the points he makes is that the team tried to reinvent the myth before it could become too hackneyed (Edward Cross, “Skyfall Exclusive: An Interview with Producer Michael G. Wilson,” www.comicbookmovie.com, February 13, 2013). Similarly, Harvey Weinstein admits he made some mistakes in promoting the movie The Master, which resulted in it not reaching its audience (Sean O’Connell, “Harvey Weinstein Admits He Mis-Marketed The Master,” www.cinemablend.com, January 29, 2013). These two statements in our opinion demonstrate a kind of humility: admitting our errors allows us to learn something that can be applied to similar situations in the future.

Shaking up the conventions

We’re coming back to ideas we’ve already discussed but with new references that provide food for thought. There’s a fine line between formula and conventions in any type of film. In his analysis of Die Hard, Darren points out that the movie worked well because it made use of all the action-film conventions without turning the script into a checklist of items to cover (Darren, “Non-Review Review: Die Hard,” them0vieblog.com, January 8, 2013).

The concept of conventions may be more difficult to transcend in the West, where stories are generally built around a clash between two or more elements that is ultimately resolved by one dominating the other. It can become difficult to develop new ideas within such a paradigm. In this context killing off the main character can be a way to gain some dramatic momentum. Unfortunately this cliché is used too often to try to breathe new life into a series, and it no longer fazes readers who know very well that the character will come back from the grave (Mike Romo, “RIP Peter Parker (Again), RIP My Faith in Marvel (Again),” http://ifanboy.com, July 1, 2013). Returning from the dead cancels out the dramatic impact and any possible learning because too often this return means a return to the status quo or to the situation that preceded the tragedy (Steve Morris, “Second Opinion: Batman # 17” http://comicsbeat.com, February 15, 2013). Morris also believes that these concepts are those of the authors and are not always consistent with the spirit of the characters or the series being developed.

One solution is offered by Mark Waid in his stories that emphasize more intimate stakes. In this sense, McMillan is targeting key elements of Hawkeye, developed by Matt Fraction: “The excitement here is that Hawkeye doesn’t wear his costume all that much and acts like a real life human being once in a while. He cracks some jokes and has some sense of his own mortality when he or his friends get shot at. He is hopeless at superheroics (i.e. fallible)” (Graeme McMillan, “What Makes Hawkeye So Special?” Newsarama, May 8, 2013). To successfully convey smaller-scale dramas, the author needs the time to develop them. Daniel Champion offers an interesting idea: “That’s ‘story’ and so often in comics, we don’t see it. A story is about something and is told through moments that happen. In comics, we only ever seem to get a bunch of things that happen, with no ‘about’ […] and that’s a waste” (Daniel Champion, “Comics is Sh*t,” www.comicbookdaily.com, January 29, 2013.). The story happens beyond the events taking place in the panels. Taking the time to develop a story can mean introducing characters that will only reveal themselves later on (Graeme McMillan, “…Who is that Again?” Newsarama, January 30, 2013).

Story twists as an obstacle course

A few months ago broadcast TV offered us the series Strike Back, which in our opinion is a lot like the series 24. The more episodes we watched, the more we would see the screenwriters stretching out the plot to make it last 12 or 24 episodes. The need to create twists and turns in the story to keep the viewer’s interest, instead of focusing on a denser storyline, makes the overall plot seem like an obstacle course. We’re not saying it makes for bad TV. On the contrary, it’s fun to watch. But we do feel it had potential that could have been drawn out more convincingly.

Similarly the plot of our story “Plunging into the Depths,” whose original title was “Race against Time,” was quite different in the first draft. The plot wasn’t even finished with 95 panels because we were writing following an obstacle-course model: a first event leading to a second, etc. However the further along we got, the less the story seemed to work. So we eliminated a lot of stuff and kept only the essential elements: the watches that might have some signification, the gadget creating an invisible protective wall, and Fabien’s strange, mystical meeting with deceased colleagues. In the end the story was much shorter, more direct, and in our opinion, much more pleasing.

Story density

In the initial story design, the secondary storyline of “Vultures” was only supposed to cover past events, and the “Exile” storyline would cover Benson’s life. However along the way we decided to use these storylines as a more direct complement to the events in the main storyline “Cycle of Shadows.” This new formula gives us more flexibility to develop the story.

Building a character

Characters should be built one layer at a time, using small touches of colour. Naturally, this approach demands both time and patience from the reader, as well as a willingness to explore the character. In Darren’s review of the film Zero Dark Thirty, we find this about one of the characters: “The “enhanced interrogation” in the film is mostly conducted by Dan, the CIA operative played by Jason Clarke. Clarke is not a low-level army officer. He’s a veteran CIA officer. He keeps (and feeds) monkeys. He has a PhD and is characterised as quite intelligent. He uses words like “tautology”, and it’s clear that he has some idea what he is doing. While he manipulates those people in his custody, he is consistently portrayed as level-headed and rational. He’s not an angry sadist lashing out some pent up frustration or aggression at a hapless victim.”

He also adds: “He might be smart, and he might be educated, but it’s clear that he has been tainted by what he is doing. Mid-way through the film, he opts to get out of the torture unit. And he complains about the death of his monkeys. It’s a moment that exists to make his priorities clear. This is a man who routinely tortures and causes suffering to human beings. At the end of it all, however, the only sympathy he has is for a bunch of monkeys” (“Who We Are In The Dark: Zero Dark Thirty & Torture…” Darren, them0vieblog.com, January 21, 2013). This is a rather deductive analysis because there are no large explanatory scenes in which the character expresses his thoughts and motivations. Viewers must bring their own interpretations to the film.

Giving your characters names

Cathy Perkins explains how, when she develops characters, she gives them names (“Building 3-D Characters,” Cathy Perkins, http://thethrillbegins.blogspot.ca, October 25, 2012). We attach a certain amount of importance to a character’s name. We give our characters short names, generally with two syllables and with a distinctive sound. This is especially true for recurring characters.

Focussing on the characters

We’ve already discussed Mark Waid at length, along with his writing techniques focusing on character rather than on large and complex machinations. We feel this is a product of our time. In his analysis of Skyfall, FamousMonster states, “The screenplay, written by John Logan, Neal Purvis, and Robert Wade, is a swaggering return to classic Bond, with an intense focus on characterization and action, as opposed to some of the more recent Bond films, which seem primarily concerned with car chases and stunt sequences” (Movie Review: Skyfall, FamousMonster, http://www.geeksofdoom.com, November 9, 2012).

A few months before, Mendes spoke similarly about the movie: “Yes, they do have a history […]. It’s much more personal story than your traditional ‘I’ve got a nuclear device and I’m going to blow up the world, Mr. Bond.’ […] You know, just making it bigger is not going to make it any more scary” (“We’ve Been Expecting You Mr. Bond,” Dan Jolin, Empire, n° 280, October 2012, p. 94-103.).

Without even being aware of it, Joss Whedon may possibly go in the same direction for his Avengers 2. “On the tone of the film, he [Whedon] said that The Avengers 2 would go deeper instead of bigger. Honestly after a huge battle like the one we saw in the first film, it be nice to get a more personal story and take a step back from the big hefty action. Apparently he wants to go so deep and personal that it will be painful.” (“Joss Whedon Talks ‘Avengers 2′ Script, ‘S.H.I.E.L.D.’ TV Show & Marvel Films,” eelyajekiM, www.geeksofdoom.com, January 11, 2013).

Timing Issues

There is a phenomenon that occurs in various forms of art (music, movies, etc.), where one artist’s production is in tune with the tastes of the day. When Mark Waid was asked about the increased interest in his work, he said, “I’m not doing anything I haven’t been doing the last 10 or 15 years in terms of how I approach story, how I approach characters, how I approach narrative. At this exact moment there seems to be room in the marketplace for stuff that is a little less formulaic and a little less like what we’ve seen before. A little less dark. A little less dystopic, without being quote-unquote “fun.” Maybe that’s what people are responding to. I don’t know” (“Interview #22 – Mark Waid,” comicsreporter.com, January 10, 2013).

The reverse can also occur: an artist can have a very successful work, and then do something similar that just doesn’t take off. This happens not only in the arts but also in any form of innovation.

Making it Exciting!

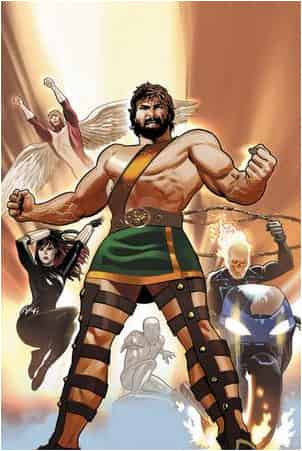

Commenting on something that Roger Stern said, Graeme McMillan looked at the failure of Marvel’s Champions series. According to Stern, the series was just a bunch of ideas aimed at developing an editorial concept without any real core concept. McMillan added that the Avengers or the Defenders could also be accused of being an editorial concept. His conclusion? The series didn’t work because it just wasn’t entertaining enough (“On ‘Fake Books’ and the Reason Behind Super-Teams,” www.newsarama.com, February 2, 2012). This is an idea that is worth talking about in greater length, so we’ll come back to it.