Bonus

-

But what were they saying? (Blitzkrieg) – Part II

-

Comic books from the 70s

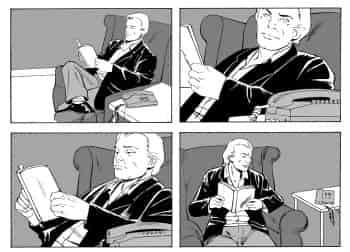

A lot of people judge American comic book writers from the 1970s harshly. Alan Moore was one of the fiercest critics of the early 80s. (“Alan Moore’s Lost Stan Lee Essay,” 1983, part 2 of 2). We consider the Silver Age to be a period in which the various elements in comic books were kept in check. The dialogue wasn’t overly explanatory, the descriptive boxes offered access to another level of story, and we hadn’t yet sunk to psychologically hyperanalyzing the characters. Here is a page from issue 200 of the Fantastic Four, written by Marv Wolfman, where we find such a balance.

-

But what were they saying? (Blitzkrieg) – Part I

-

Collaboration between writers and illustrators

We have already spoken of the symbiosis that exists between words and illustration, but the relationship can sometimes be even more profound. Take, for example, the collaboration between Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli for the Daredevil series in the 1980s. Nadel says, “Very simply, the story follows Matt Murdoch/Daredevil as his life is dismantled by his nemesis, The Kingpin. He loses faith in himself and the world, then regains it. Miller conceived the story and then he and Mazzucchelli collaborated very closely, as described by the artist in his unexpectedly candid and moving introduction: ‘This is why we chose not to separate the credits into writer and artist; because although technically I did no scripting and Frank did no drawing, I was contributing ideas for plot, characterization, and storytelling (such as the succession of title pages charting Matt’s descent), while Frank was describing the contents of each panel in his scripts’ ” (“Some Thoughts on David Mazzucchelli’s Daredevil: Born Again Artist’s Edition,” Dan Nadel, www.tcj.com, August 27, 2012).

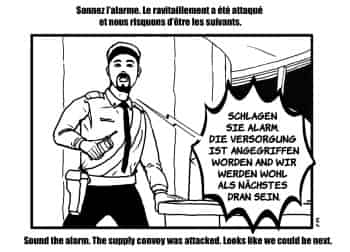

To illustrate, when Michel Lamontagne suggested that we write a story from the point of view of the villains, we found the concept interesting. This resulted in “Blitzkrieg.” This story puts a face to some of the characters who often remain anonymous, and shows some of the human repercussions of the Black Orchestra’s attacks.

-

The art of subtraction

Matthew E. May believes that, “The art of limiting information is really about letting people write their own story, which becomes much more engaging and powerful because they’ve invested their own intelligence and imagination and emotion” (“Want To Spark Innovation? Think Like a Cartoonist,” Matthew E. May, www.fastcompany.com, October 15, 2012).

Instinctively, we try to remove information to let the reader create his own scenes, hoping that the reader imagines reactions similar to those we want to produce. For example, in this scene, we could have added a lot of internal dialogue for Valasquez, but we preferred to leave some blanks. In fact, we like to write as little as we possibly can.