TV and movie

Interpreting Captain America

We’ve confessed it before and we’ll say it again: Captain America was (is still) our favourite superhero. When we saw the first movie Marvel dedicated to him, we felt uncomfortable seeing him holding a gun, but we couldn’t quite figure out why. Then we came across this interpretation by Chris Sims. We totally agree with his analysis:

“One of the things I really like about this story is how much importance Kirby puts onto the idea of Cap’s shield as a symbol. I love that, because it underscores one of my favorite things about the character: He’s a soldier who doesn’t carry a gun. He carries a shield, because he exists to protect and defend people against the forces that would hurt them. It’s one of the most elegant ideas in comics, and something that I think really plays into Kirby’s idealized vision of what America should be […] It’s a big symbol, and in Cap’s view—and Kirby’s—that symbol has a lot of power. “(Chris Sims, “Ask Chris #156: KILL-DERBY!” July 5, 2013, http://comicsalliance.com.)

Reading this, we wonder if the creators had all those ideas explicitly, or if these concepts were unconscious and only waiting to emerge. The second Captain America movie (“The Winter Soldier”) was much more consistent with this definition of Cap’s character.

Trading in one form of fanaticism for another

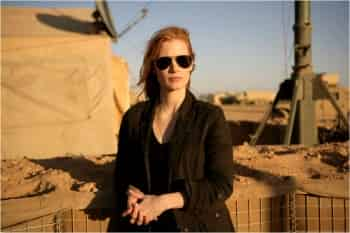

We’ve already talked about the film Zero Dark Thirty, but a few months ago we came across a critique of the DVD release in which the author discusses Maya, the hero of the film: “Her fanatical pursuit of Bin Laden helps to neutralise ordinary moral qualms… This awareness of the torturer’s hurt sensitivity as the (main) human cost of torture ensures that the film is not cheap rightwing propaganda: the psychological complexity is depicted so that liberals can enjoy the film without feeling guilty. This is why Zero Dark Thirty is much worse than 24, where at least Jack Bauer breaks down at the series finale. “

We find the idea of one form of fanaticism being replaced by another very interesting, and more so that the story can allow viewers to detach from a conflict that would normally affect them (Slavo Zizek, “Zero Dark Thirty: Hollywood’s Gift to American Power,” The Guardian, Friday, January 25, 2013).

Story twists as an obstacle course

A few months ago broadcast TV offered us the series Strike Back, which in our opinion is a lot like the series 24. The more episodes we watched, the more we would see the screenwriters stretching out the plot to make it last 12 or 24 episodes. The need to create twists and turns in the story to keep the viewer’s interest, instead of focusing on a denser storyline, makes the overall plot seem like an obstacle course. We’re not saying it makes for bad TV. On the contrary, it’s fun to watch. But we do feel it had potential that could have been drawn out more convincingly.

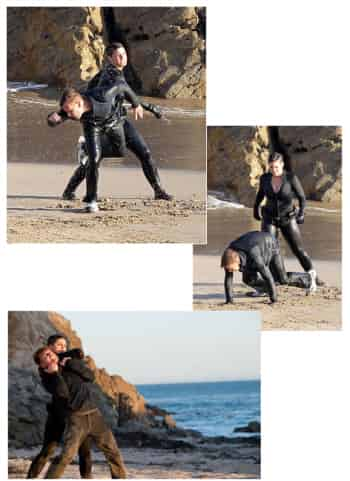

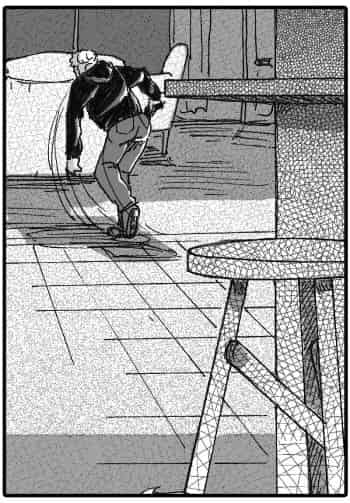

Similarly the plot of our story “Plunging into the Depths,” whose original title was “Race against Time,” was quite different in the first draft. The plot wasn’t even finished with 95 panels because we were writing following an obstacle-course model: a first event leading to a second, etc. However the further along we got, the less the story seemed to work. So we eliminated a lot of stuff and kept only the essential elements: the watches that might have some signification, the gadget creating an invisible protective wall, and Fabien’s strange, mystical meeting with deceased colleagues. In the end the story was much shorter, more direct, and in our opinion, much more pleasing.

Building a character

Characters should be built one layer at a time, using small touches of colour. Naturally, this approach demands both time and patience from the reader, as well as a willingness to explore the character. In Darren’s review of the film Zero Dark Thirty, we find this about one of the characters: “The “enhanced interrogation” in the film is mostly conducted by Dan, the CIA operative played by Jason Clarke. Clarke is not a low-level army officer. He’s a veteran CIA officer. He keeps (and feeds) monkeys. He has a PhD and is characterised as quite intelligent. He uses words like “tautology”, and it’s clear that he has some idea what he is doing. While he manipulates those people in his custody, he is consistently portrayed as level-headed and rational. He’s not an angry sadist lashing out some pent up frustration or aggression at a hapless victim.”

He also adds: “He might be smart, and he might be educated, but it’s clear that he has been tainted by what he is doing. Mid-way through the film, he opts to get out of the torture unit. And he complains about the death of his monkeys. It’s a moment that exists to make his priorities clear. This is a man who routinely tortures and causes suffering to human beings. At the end of it all, however, the only sympathy he has is for a bunch of monkeys” (“Who We Are In The Dark: Zero Dark Thirty & Torture…” Darren, them0vieblog.com, January 21, 2013). This is a rather deductive analysis because there are no large explanatory scenes in which the character expresses his thoughts and motivations. Viewers must bring their own interpretations to the film.

Inconsistencies and story

We’ve already mentioned the inconsistencies can be deliberately left in a scene to amplify mystery or even realism, since after all, we don’t always behave logically. But other inconsistencies may not necessarily be voluntary. In his analysis of the character of Goldfinger in the movie of the same name, Darren notes the following: “Like a lot of Goldfinger’s actions over the course of the film, one wonders why he didn’t just ask Oddjob to remove the gold from the car before he crushed it. After all, Solo was dead and unlikely to complain. Perhaps, like the rest of Goldfinger’s somewhat contradictory actions, it just allows the man to show off, feeding into his desire for attention and his demands for respect. Perhaps he just gets a giddy thrill at the idea that his gold blocks have mingled with a mushed-up gangster” (A View to a Bond Baddie: Auric Goldfinger, Darren, them0vieblog.com, October 4, 2012).

The French-language Wikipedia page on the movie Once Upon a Time in the West brings up similar questions about an injury suffered by Charles Bronson’s character. One of the theories is that the script wasn’t well understood during the editing process.

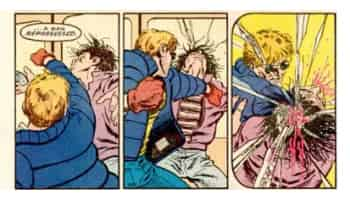

In the box below, taken from our story ” A Man to Kill,” we see Chad getting up but he has his back to the action when he should have been facing it. This is one inconsistency that got past us, despite several production stages.

Comments from fans

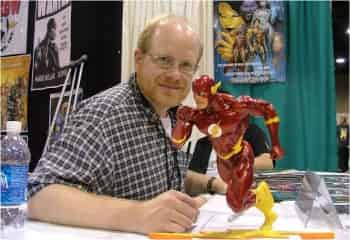

In an interview by e-zine The Beat, Bill Jemas, founder of 360eps and former member of the Marvel team, said: “You can be more creative for less money and less time with better feedback with comics than in any medium I’ve ever been around” (“Interview: Former Marvel COO Bill Jemas Tells Us How to Wake the F#ck Up,” comicsbeat.com, September 13, 2012). This is in line with Marc Alan Fishman saying that he managed the risks of his creative projects by listening to the comments of his true fans (“Everything We Do, We Do It for You,” Marc Alan Fishman, comicmix.com, October 27, 2012).

Without denying the value of fan comments, it’s important to know what changes are being made to improve the product and which ones are done just to make readers happy. Jesse Alexander called the third season of the TV series Alias definitely the series’ worst: “[…] and we’d change up things a little based on viewers’ reactions to certain things. But because we didn’t have any chance to deal with that the year [season four], we’ve been operating in a vacuum where we’ve really been free to craft a story without any outside influence. I think that’s probably helped us stay focused on our goal for the end of the year” (“Revelations,” Alias–The Official Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 10, May-June 2005, p.64-65).

The point isn’t to reject readers’ comments; quite the opposite. But if we write, it’s because we have something to say. As Mark Waid said, you have to please yourself and it all depends more or less on you if down the line your work is read by a lot of other people (Interview #22 – Mark Waid, www.comicsreporter.com, January 10, 2013).

Managing your concepts

In a blog entry on the film Promised Land, François Cardinal made the following comment: “I simply received confirmation for what I have long believed: the environment rarely makes for good writing, simply because the author’s beliefs take centre stage, at the expense of the story. ” [translation]. (« Terre promise : quand la fiction se met au service de l’écologie… », lapresse.ca, Monday, January 7, 2013).

Burlingame, who was covering a number of writing rules, said: “Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.” (“Pixar and Joss Whedon’s Rules For Writers,” Russ Burlingame, comicbook.com, December 8, 2012).

We completely agree with both these statements. In fact, we think that when writers give their opinion through their characters, it takes away from the fiction and turns the story into an essay, which is a completely different literary form. It is also a type of fraud toward the readers, to whom the writer promises entertainment, but then slowly attempts to brainwash them with faddish personal beliefs.

We also believe that manipulating ideas must be done very delicately in a work of fiction. In his analysis of the movie, The Dark Knight Rises, Sebala emphasizes that “The Dark Knight Rises suffers so mightily because it substitutes twists for character arcs, convenience for hard choices and flashbacks for discernible themes” (Sound and Fury: ‘The Dark Knight Rises’ Against Theme and Story, Christopher Sebela, comicsalliance.com, July 27, 2012). In this way, a writer’s good ideas can suffocate the story, at the expense of the characters and of the story.

Peppering the story with events to create movement

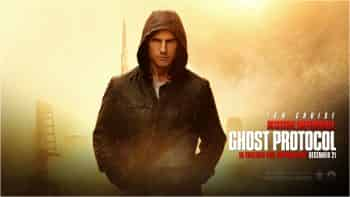

A few months ago, we watched the fourth installment in the Mission Impossible series, and we couldn’t help but ask, “Why?” with each passing scene: why are all the operations, which are supposed to make the team’s mission move forward, ending up in failure? Especially when another course of action that was possible at the beginning of the scene would have allowed them to achieve the same goal? For example, after their mission to get into the Kremlin to discover a criminal’s identity doesn’t succeed, the big boss then comes along and tells them who the bad guy is. So why take such a roundabout path when a shortcut is available? Certainly, we understand the challenges faced by a writer who has to create an adventure that fits into a given time format. But such a convoluted storyline doesn’t seem a great way to create suspense. As it says in Pixar’s “22 Rules of Storytelling,” “Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.” (“Pixar and Joss Whedon’s Rules for Writers,” Russ Burlingame, comicbook.com, December 8, 2012).

Which tone to use?

Corey Schroeder reminds us that “Fast-forward to the 90s and you’ve got a new kind of Batman. Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns have reinvented superheroes as real people with real flaws in the midst of stories that treat the audience’s intellect with maturity” (“Are Superhero Comics Too Serious,” www.comicvine.com, September 14, 2011). Chris Sims goes even further: “The imitators learned the wrong lessons, and instead of creating stories that treated their subject matter with intelligence and craft, which is a difficult matter requiring a great deal of skill, the knock-offs tried to recapture the things that were easy, like cussin’ and violence. They were exactly the same kind of escapist power fantasy that they were pretending to rise above, just wrapped up in cheap, meaningless exploitation and sold to the audience as something that wasn’t for little kids — which in itself is the most immature, teenage motivation something can possibly have” (“What’s Up with the 90s?” www.comicsalliance.com, July 27, 2012).

This may explain why some people wonder if superhero stories have become too violent (“Sex & Violence,” www.comicbookdaily.com, December 9, 2011). In our opinion, violence isn’t the real problem. In the 90s, Frank Miller’s Daredevil stories included some very graphic representations of violence. But they fit the mood. Our main reproach would be the lack of perspective about that violence. If we take the TV series 24, Jack Bauer tortured criminals but we don’t recall any innocent characters being tortured. We feel more uneasy about that situation than about the torture itself.