Writing

Ideas floating in the air– Part I

Today, it’s hard to create something that’s fundamentally original. Stanley Kubrick is said to have told Jack Nicholson, “You know, in a way every scene has already been done in film. Our job is simply to do them a little better” (Kubrick, Michel Ciment, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1999, p. 297). Now that we all have easy access to the accumulated knowledge of centuries, it’s hard to pretend that knowledge doesn’t exist.

In an interview, Sam Mendes said Nolan’s Dark Knight was a revelation in his approach to the latest James Bond (“The Dark Knight Skyfall: New Bond Director Drew Inspiration from Nolan’s Batman,” Russ Burlingame, October 19, 2012). But at the same time, Darren, in his analysis, shows that Nolan’s Batman owes a great debt to the Bond franchise: “What Bond Learned from Batman: The Dark Knight & Skyfall […]” (Darren, them0vieblog.com, October 26, 2012). He adds that these dynamics of mutual influence should not be avoided, but we must learn to draw the right lessons from them.

Comments from fans

In an interview by e-zine The Beat, Bill Jemas, founder of 360eps and former member of the Marvel team, said: “You can be more creative for less money and less time with better feedback with comics than in any medium I’ve ever been around” (“Interview: Former Marvel COO Bill Jemas Tells Us How to Wake the F#ck Up,” comicsbeat.com, September 13, 2012). This is in line with Marc Alan Fishman saying that he managed the risks of his creative projects by listening to the comments of his true fans (“Everything We Do, We Do It for You,” Marc Alan Fishman, comicmix.com, October 27, 2012).

Without denying the value of fan comments, it’s important to know what changes are being made to improve the product and which ones are done just to make readers happy. Jesse Alexander called the third season of the TV series Alias definitely the series’ worst: “[…] and we’d change up things a little based on viewers’ reactions to certain things. But because we didn’t have any chance to deal with that the year [season four], we’ve been operating in a vacuum where we’ve really been free to craft a story without any outside influence. I think that’s probably helped us stay focused on our goal for the end of the year” (“Revelations,” Alias–The Official Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 10, May-June 2005, p.64-65).

The point isn’t to reject readers’ comments; quite the opposite. But if we write, it’s because we have something to say. As Mark Waid said, you have to please yourself and it all depends more or less on you if down the line your work is read by a lot of other people (Interview #22 – Mark Waid, www.comicsreporter.com, January 10, 2013).

Managing your concepts

In a blog entry on the film Promised Land, François Cardinal made the following comment: “I simply received confirmation for what I have long believed: the environment rarely makes for good writing, simply because the author’s beliefs take centre stage, at the expense of the story. ” [translation]. (« Terre promise : quand la fiction se met au service de l’écologie… », lapresse.ca, Monday, January 7, 2013).

Burlingame, who was covering a number of writing rules, said: “Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.” (“Pixar and Joss Whedon’s Rules For Writers,” Russ Burlingame, comicbook.com, December 8, 2012).

We completely agree with both these statements. In fact, we think that when writers give their opinion through their characters, it takes away from the fiction and turns the story into an essay, which is a completely different literary form. It is also a type of fraud toward the readers, to whom the writer promises entertainment, but then slowly attempts to brainwash them with faddish personal beliefs.

We also believe that manipulating ideas must be done very delicately in a work of fiction. In his analysis of the movie, The Dark Knight Rises, Sebala emphasizes that “The Dark Knight Rises suffers so mightily because it substitutes twists for character arcs, convenience for hard choices and flashbacks for discernible themes” (Sound and Fury: ‘The Dark Knight Rises’ Against Theme and Story, Christopher Sebela, comicsalliance.com, July 27, 2012). In this way, a writer’s good ideas can suffocate the story, at the expense of the characters and of the story.

Making a plan and being able to deviate from it – Part 2

The story “The Transaction” wasn’t in our initial plan. It was added to plug a temporal gap between two significant events in the storyline. The character of Balthazar was developed for that purpose. In fact, many of the stories from 1993 and 1994 were created to fill that gap. Editor Jordan D. White gives a good overview of the situation: “But it’s always important to keep those long-term plans as loose as possible—there is a really good chance that by the time we finish writing the first arc, we’re going to have a different idea of where we’re going than we started with—or at least a different idea of how to get there” (“Jordan D. White Reveals the Secrets of Editing,” Steve Morris, comicsbeat.com, October 21, 2012).

Making a plan and being able to deviate from it – Part I

At the end of his time at Marvel, where he mainly worked on the Captain America series, Ed Brubaker said the following: “I hoped for two years, and planned for three, because three years was about the longest I’d stayed on any other book. My pitch document had the first 12 issues mapped out, which I mostly stuck to, actually, and then sketched out the next year in broad strokes. I never imagined I’d go even 50 issues, let alone the I think 102 issues I did, counting mini-series and one-shots and annuals.” He also added, “More than anything, it was that each issue kept wanting to be longer or I kept feeling like I had more ideas and wanted to spend more time with the characters, and realized I was stopping myself from doing that with an arbitrary structure I’d imposed on myself” (“The Ed Brubaker ‘Captain America’ Exit Interview,” David Brothers, comicsalliance.com, November 1, 2012).

There are two opposing ideas here: the idea of a plan that guides the author, and the idea of the flexibility the writer must maintain to include new ideas or developments that hadn’t been originally anticipated. In our project, one of the ideas that just evolved like that was Votan’s identity. At first, he was going to remain mysteriously anonymous over a number of stories, if not all the way to the end, but ultimately, we dropped that concept, preferring instead to reveal his identity quickly, because this opened up more dramatic opportunities.

Peppering the story with events to create movement

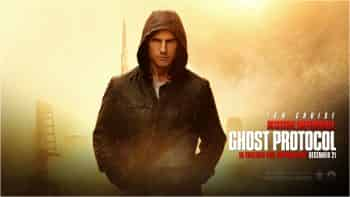

A few months ago, we watched the fourth installment in the Mission Impossible series, and we couldn’t help but ask, “Why?” with each passing scene: why are all the operations, which are supposed to make the team’s mission move forward, ending up in failure? Especially when another course of action that was possible at the beginning of the scene would have allowed them to achieve the same goal? For example, after their mission to get into the Kremlin to discover a criminal’s identity doesn’t succeed, the big boss then comes along and tells them who the bad guy is. So why take such a roundabout path when a shortcut is available? Certainly, we understand the challenges faced by a writer who has to create an adventure that fits into a given time format. But such a convoluted storyline doesn’t seem a great way to create suspense. As it says in Pixar’s “22 Rules of Storytelling,” “Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.” (“Pixar and Joss Whedon’s Rules for Writers,” Russ Burlingame, comicbook.com, December 8, 2012).

In “A Dead Man,” why doesn’t Jason react after he stabs Tucker?

Some of our readers wanted to know why Jason just stood frozen while Tucker plunged into the ocean (in “A Dead Man”). We really don’t have an answer for this. The scene came to us like that and we thought it worked well, particularly since it is imbued with a strong sense of the illogical.

Also, initially, Jason was supposed to shoot Tucker with a small firearm hidden on his calf. We changed this for a knife because it requires direct contact. A gun would have allowed Jason to fire on Tucker as he disappeared into the water.

Team-centred stories

Tony Guerrero said that, in team stories, the disappearance of one character didn’t really have an impact (“When Main Characters Disappear from their Comic Books,” www.comicvine.com, April 10, 2012). On the other hand, Guerrero had said, a few weeks before that, that this type of situation held the most suspense because it’s more difficult for the reader to predict the outcome (“Does Knowing The Hero Always Wins Affect Reading Enjoyment?” www.comicvine, March 20, 2012).

Writing tips

Several blogs offer tips to help beginning writers develop their skills. Here are a few that caught our attention:

John Ostrander’s theory: “It’s what I call the ‘iceberg theory.’ The bulk of an iceberg is underwater. That bulk is necessary for the part of the iceberg that shows. In the same way, you need to know a lot about the characters, the setting, the story but only a certain percentage of it needs to show. So you select which details help make the story real and convincing to the reader. Those are the telling details” (“Details, Details, Details,” www.comicmix.com, July 15, 2012).

While Emily S. Whitten didn’t set out to give writing tips in her post, she still offers good advice: “Civil War is one of my favorite comic book crossovers for several reasons. One is that this is a crossover in which every character has a legitimate reason to be involved” (“Marvel Civil War – Prose vs. Graphic Novel,” www.comicmix.com, July 17, 2012).

Because writing a comic also involves drawing, Daniel Champion gives the following tips: 1) Have an eye to finding the weaknesses in others’ writing and try to understand why it doesn’t work. 2) Understand how two or three panels “talk to each other” (“Drawing for Comics,” www.comicbookdaily.com, July 10, 2012).

Terrassa Iezzi suggests forgetting about the average reader, which will only lead to a pre-digested product (“Why You Love ‘The Wire,’ Explained in Fascinating Detail,” www.fastcompany.com,). We might add that each author should be his or her own primary reader. You should ask yourself what you like to read. If you can’t find your own work interesting, it will be difficult to get other’s attention.

And lastly, in another column, Daniel Champion gives these additional tips: 1) Write the end in minute detail before starting to write your story. 2) Be unpredictable. And, especially, 3) Watch Lost and understand it! (“Writing for Comics”—“Across the Pond” www.comicbookdaily.com, July 18, 2012).

Which tone to use?

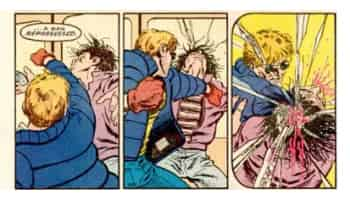

Corey Schroeder reminds us that “Fast-forward to the 90s and you’ve got a new kind of Batman. Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns have reinvented superheroes as real people with real flaws in the midst of stories that treat the audience’s intellect with maturity” (“Are Superhero Comics Too Serious,” www.comicvine.com, September 14, 2011). Chris Sims goes even further: “The imitators learned the wrong lessons, and instead of creating stories that treated their subject matter with intelligence and craft, which is a difficult matter requiring a great deal of skill, the knock-offs tried to recapture the things that were easy, like cussin’ and violence. They were exactly the same kind of escapist power fantasy that they were pretending to rise above, just wrapped up in cheap, meaningless exploitation and sold to the audience as something that wasn’t for little kids — which in itself is the most immature, teenage motivation something can possibly have” (“What’s Up with the 90s?” www.comicsalliance.com, July 27, 2012).

This may explain why some people wonder if superhero stories have become too violent (“Sex & Violence,” www.comicbookdaily.com, December 9, 2011). In our opinion, violence isn’t the real problem. In the 90s, Frank Miller’s Daredevil stories included some very graphic representations of violence. But they fit the mood. Our main reproach would be the lack of perspective about that violence. If we take the TV series 24, Jack Bauer tortured criminals but we don’t recall any innocent characters being tortured. We feel more uneasy about that situation than about the torture itself.