Writing

Story Credibility

In one of our past comments, we wondered what makes a story entertaining. The characters are definitely a key component. Mandy Newell looks at what makes a character a good one. Quoting Lawrence Block, she identifies that a great character is three things: plausible, sympathetic and original (“Character,” www.comicmix.com, March 12, 2012). Newell then looks more closely at the idea of characters being sympathetic. But we want to spend some time on the idea of plausibility—and we much prefer the term “credibility.”

On this idea, we cite Jozef Siroka’s analysis of the film Warrior, where he says that “Like Spike Lee, O’Connor never uses the social themes as a facile way to punctuation emotion or to make populist claims. Instead his message is structured around credible, nuanced and likeable characters facing the day-to-day problems most of us can relate to [translation]” (« Warrior: noble retour à l’état primitif », www.lapresse.com , January 31, 2012).

But some might reply that battling monsters, robots and bloodthirsty killers is nothing like most people’s day-to-day problems. And that’s exactly why we prefer the term “credible” to “plausible.” Credibility requires the reader to accept the conventions of the universe being explored. The Lord of the Rings is not plausible, but the consistency of Tolkien’s world makes it credible, and the reader can connect with the characters through their emotions.

On Tone

When Spurgeon interviewed Ed Brubaker (“CR Sunday Interview: Ed Brubaker,” www.comicsreporter.com, June 24, 2012) he offered this introduction to one of his questions: “When I read a bunch of your Captain America recently, I was surprised how somber it was. I don’t mean that it was depressing or sad, I mean serious and sober.”

We came across this sentence a long time after we’d started writing and we felt that it was in keeping with what we are trying to do. Our dialogue is imbued with restraint—some would even say banality, and we accept that. Our goal isn’t to write transcendent dialogue. Instead we want to convey ambiguous moods, as though the characters were unable to reconcile all the mysteries around them or all the lies they’ve told others and themselves.

Writing Challenges : Divide and Conquer – Part I

This story is constructed in two sections. First, there is a description of the location, and then the events accelerate and omissions are made to compress the action. Also, the script does not contain a lot of dialogue. That’s because Benson is a consummate professional, so he doesn’t need to say his feelings and questions out loud.

Let the reader discover the story : The exemple of The Wire

This comment comes from Terressa Lezzi in her discussion of an academic video that looks at the TV series The Wire: “The result of this style was a show that allowed viewers the satisfaction of discovering the beauty of a story, instead of having it explicitly and repeatedly pointed out of them” (“Why You Love The Wire, Explained in Fascinating Detail,” www.fastcompany.com).

Marc Alan Fishman was talking along the same lines when he said the best comics are those that take the time to really present their concept in as many as five or six issues (“How To Succeed in Comics Without Really Trying,” www.comicbookdaily.com, February 25, 2012). In an interview, Brian K. Vaughan similarly said he hadn’t written a big twist at the end of the first issue of the SAGA series (“Interview: Brian K. Vaughan on SAGA, Lost, Twitter and more,” The Beat, comicsbeat.com, March 14, 2012). We naturally agree with this point of view, but we’ll see in future comments that others favour a much more direct approach.

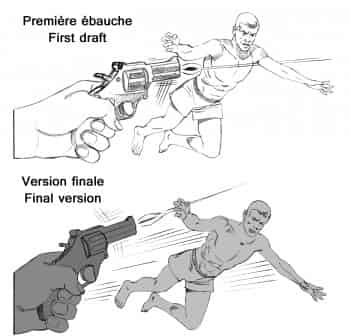

Avoiding Overdramatic

In the story, “A Firm Offer,” our original idea was the opposite of what comes to pass in the final version. We had planned to have Wade somehow learn that Eva had been unfaithful. There would have been a violent scene, where Wade hits his wife. Blascovitch would have arrived and defended Eva, or even killed Wade.

Naturally, we prefer our final script, where Eva isn’t a victim who makes a decision in the heat of the moment. When Brookbank and Blascovitch make her an offer, she analyzes the situation coolly, and it’s her own ambition that leads her to turn her back on her life. We feel that, in this scene, Eva gains more personality, which creates some interesting dramatic potential.

The Story’s Consistency Challenge

Wood was originally featured in the first script, “Letdown,” but as a silent actor. We wanted to introduce him to let the reader know that he had been in the world of our main characters for some time, so that when Brookbank selected him for a position in the Black Orchestra, it wouldn’t seem to come out of nowhere. But this created a problem in the later story, “Spatter.” There, when Wood introduces himself to Eva, it seems like they are meeting for the first time. So we decided to edit Wood from the earlier story.

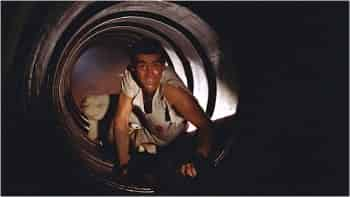

References in Plain View

We are constantly bombarded by stories (TV, movies, newspapers, books, etc.). Unconsciously or even deliberately, we borrow ideas we’ve seen elsewhere and insert them into our stories. So in the story, “The Test,” we reuse the tunnel that heats up and the electric grate from Doctor No. Surely many people recognized it. We didn’t try to hide that we were borrowing it. In fact, Jason explicitly refers to it in one of his one-liners.

So, you read minds then?

On the Web, there are a lot of critics bemoaning the fact that recent comic books are much faster reads than they were in the 60s and 70s. Should this bother us? We certainly don’t think so. Those older comics were often overwritten, with bubbles narrating what was already clear in the illustrations. And thought bubbles became an easy way to explain what was going on—often at the expense of suspense. In the movies, we only get access to characters’ thoughts y illustrated. In movies (that don’t resort to the use of voiceover), characters’ thoughts are mainly conveyed to the audience by way of powerful images. This can create much stronger scenes because they give viewers some freedom of interpretation. So, for our comic, we gave ourselves the goal of not saying what the illustrations already show. And that’s why you won’t see us resorting to thought bubbles.