Writing

Levels of violence

A few months ago, Mark Waid stated, “Writing evil and writing violence, if you’re clever and do it right, can be two entirely different sets of visuals.” At the same time, Waid said he was sorry he had killed some of the characters he had created (DC Comics: Allegations of Editorial Strong-Arming in the Old 52, Russ Burlingame, comicbook.com, August 26, 2012). Without making excuses, we see different levels in the deaths of characters. At the lowest level of the pyramid, there is cannon fodder: interchangeable henchmen who are regularly eliminated or captured and who are totally anonymous. Their anonymity means that their death has no repercussions, since they were never truly alive for the reader. A little higher up are the villains whose death is the ultimate punishment for their misdeeds. We find this type of sacrificed lambs more problematic, since they are brought into the story to trigger a reaction from the hero, and their death aims to produce a dramatic effect. In some stories, like the James Bond movies, to give only one example, these characters are so predictable that we as viewers choose not to get attached to them. And lastly, there is the level at which a character’s death, whether or not it is natural, represents that character’s culmination. Violence is one thing, and having a character evolve is another, even if that requires the death of someone from his or her entourage.

Comic books from the 70s

A lot of people judge American comic book writers from the 1970s harshly. Alan Moore was one of the fiercest critics of the early 80s. (“Alan Moore’s Lost Stan Lee Essay,” 1983, part 2 of 2). We consider the Silver Age to be a period in which the various elements in comic books were kept in check. The dialogue wasn’t overly explanatory, the descriptive boxes offered access to another level of story, and we hadn’t yet sunk to psychologically hyperanalyzing the characters. Here is a page from issue 200 of the Fantastic Four, written by Marv Wolfman, where we find such a balance.

Collaboration between writers and illustrators

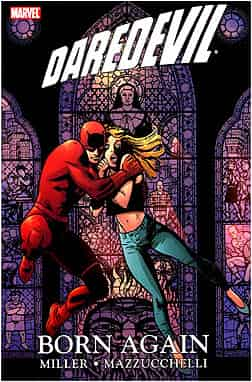

We have already spoken of the symbiosis that exists between words and illustration, but the relationship can sometimes be even more profound. Take, for example, the collaboration between Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli for the Daredevil series in the 1980s. Nadel says, “Very simply, the story follows Matt Murdoch/Daredevil as his life is dismantled by his nemesis, The Kingpin. He loses faith in himself and the world, then regains it. Miller conceived the story and then he and Mazzucchelli collaborated very closely, as described by the artist in his unexpectedly candid and moving introduction: ‘This is why we chose not to separate the credits into writer and artist; because although technically I did no scripting and Frank did no drawing, I was contributing ideas for plot, characterization, and storytelling (such as the succession of title pages charting Matt’s descent), while Frank was describing the contents of each panel in his scripts’ ” (“Some Thoughts on David Mazzucchelli’s Daredevil: Born Again Artist’s Edition,” Dan Nadel, www.tcj.com, August 27, 2012).

To illustrate, when Michel Lamontagne suggested that we write a story from the point of view of the villains, we found the concept interesting. This resulted in “Blitzkrieg.” This story puts a face to some of the characters who often remain anonymous, and shows some of the human repercussions of the Black Orchestra’s attacks.

The art of subtraction

Matthew E. May believes that, “The art of limiting information is really about letting people write their own story, which becomes much more engaging and powerful because they’ve invested their own intelligence and imagination and emotion” (“Want To Spark Innovation? Think Like a Cartoonist,” Matthew E. May, www.fastcompany.com, October 15, 2012).

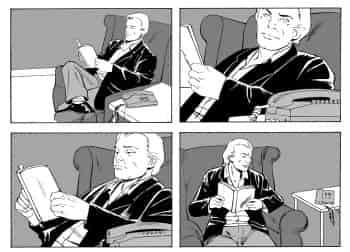

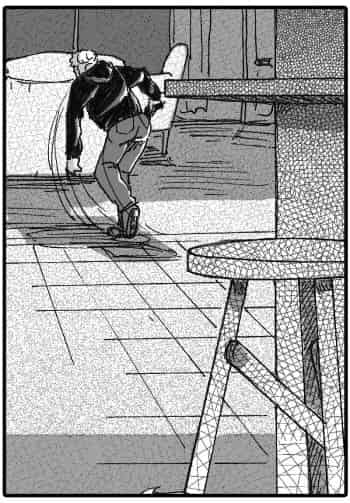

Instinctively, we try to remove information to let the reader create his own scenes, hoping that the reader imagines reactions similar to those we want to produce. For example, in this scene, we could have added a lot of internal dialogue for Valasquez, but we preferred to leave some blanks. In fact, we like to write as little as we possibly can.

Respecting the characters

Here’s what Sara Lima had to say about Power Girl: “There’s nothing wrong with Power Girl’s old costume. I really felt it was okay for PG to show cleavage with the hole in her suit if it meant that in her comic she would be treated with a certain level of dignity; which is what we had in Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray’s self-titled POWER GIRL series. I would argue that Power Girl is more “cheesecake” now than ever before, and it’s getting ridiculous. The fact that her suit is torn to shreds in every issue seems to be some kind of running joke—and it’s getting really tired. It feels like the writer doesn’t have respect for the character. What other purpose does her character serve aside from being there to get naked? It feels tawdry. For whatever reason, rather than giving PG her old costume back, someone feels it’s more interesting to tear up her new one” (“What’s Wrong with the Huntress and Power Girl in the ‘New 52’?” Sara Lima, October 18, 2012, www.comicvine.com).

What we like in this tirade is the use of the word “dignity.” We must in fact grant our characters a form of respect, not only to avoid running gags about them but also to respect their actions, especially their most objectionable ones. This doesn’t mean that the writer approves of these actions but simply, that if they can’t be avoided, these actions must be consistent with the character’s nature.

Writing tips – Part II

Everyone has advice for story writers. We feel that Miranda Parker makes a very apt recommendation: “At the same time, don’t give yourself away. If you don’t know, don’t go there. My rule of thumb is, if I don’t know something without looking it up, I’m usually better off working around it. When you drop in undigested research morsels, the reader can feel it in his teeth” (“Don’t Write What You Know. Write Like You Know,” Miranda Parker, J. Mark Bertrand, thethrillbegins.blogspot.ca, September 20, 2012).

We spent months researching an illness for Cordo: one that would be incurable, that would advance relatively quickly but whose progress could be slowed. We didn’t find anything conclusive, and in the end, we decided to keep the illness vague rather than become mired in pointless explanations. Ultimately, we don’t think the story suffers from it.

Inconsistencies and story

We’ve already mentioned the inconsistencies can be deliberately left in a scene to amplify mystery or even realism, since after all, we don’t always behave logically. But other inconsistencies may not necessarily be voluntary. In his analysis of the character of Goldfinger in the movie of the same name, Darren notes the following: “Like a lot of Goldfinger’s actions over the course of the film, one wonders why he didn’t just ask Oddjob to remove the gold from the car before he crushed it. After all, Solo was dead and unlikely to complain. Perhaps, like the rest of Goldfinger’s somewhat contradictory actions, it just allows the man to show off, feeding into his desire for attention and his demands for respect. Perhaps he just gets a giddy thrill at the idea that his gold blocks have mingled with a mushed-up gangster” (A View to a Bond Baddie: Auric Goldfinger, Darren, them0vieblog.com, October 4, 2012).

The French-language Wikipedia page on the movie Once Upon a Time in the West brings up similar questions about an injury suffered by Charles Bronson’s character. One of the theories is that the script wasn’t well understood during the editing process.

In the box below, taken from our story ” A Man to Kill,” we see Chad getting up but he has his back to the action when he should have been facing it. This is one inconsistency that got past us, despite several production stages.

Compression and decompression

“We don’t often spend enough time on ramifications in mainstream comics, so here was a place to build a whole storyline around them.” —Ed Brubaker (“The Ed Brubaker ‘Captain America’ Exit Interview,” David Brothers, comicsalliance.com, November 1, 2012).

Brubaker’s statement reminded us of a piece written by Renaud Pasquier (« “Homeland” met en scène le nouveau Jack Bauer de l’Amérique parano », Le Nouvel Observateur, September 29, 2012), in which he analyzes the first season of the TV series Homeland: ” However, this story won’t at all engage in a furious investigation fueled by the fateful ticking of the clock. What gives fiction its rhythm is time, not external or mechanical time, but something intimate and organic. The irregular and non-linear time of experience; the time of suspicions, doubts and hesitations; the time of emotions, thoughts and memories; but also, the time of delusions” [translation].

In an interview with Mark Waid, Tom Spurgeon used the word “decompression” to talk about Waid’s writing style (Interview # 22 – Mark Waid, www.comicsreporter.ccom, January 10, 2013). We like the image the word creates. We’d like to refine this a little and suggest there is an analogy to be made with the accordion: you need to let air into the instrument (decompression) in order to produce sounds (compressions). If our stories operate only in action mode (compression), they can no longer breathe, there is no longer time to come to understand the characters, their motivations, their evolution. Compression and decompression: that’s our recipe.

Ideas floating in the air– Part III

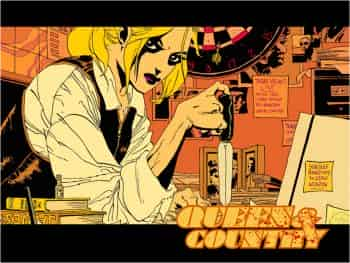

We start our stories off by showing the faces and names of the main characters, to help the readers identify the actors in that particular story, but also because the look of the characters may change slightly depending on who is illustrating it. The other benefit of this approach is that it saves us from having to use up panels to present the characters again, allowing us to showcase more direct conversation between them. Recently, while reading a Queen & Country comic book by Greg Rucka (developed by him in the late 2000s), we noticed that it used a similar approach.

Now, let’s talk about the last James Bond film, where the spy’s weapon won’t work if the fingerprints on the hand holding it don’t match the owner’s. We wrote something like this in Divide to Conquer a long time before we saw Skyfall. In our story Grant uses a similar device for his weapon.

What we’re trying to show here is that ideas may be used by several writers without necessarily having been copied. Sometimes this happens by accident, simply because ideas float around in the air at certain times, waiting to emerge. Two writers may have tuned into them at separate times without being aware of it.

Ideas floating in the air– Part II

A discussion took place on the web about Alan Moore having “borrowed” for a Superman story that was allegedly inspired by Grant Morrison’s Superfolks series. The author of this piece theorizes that Alan Moore may have unconsciously drawn from ideas that had struck him many years before (“Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 2: The Case for the Defence,” comcisbeat.com, November 11, 2012). In our story, “World’s Best Friends,” Benson makes a comment about his father’s upcoming death. It was only months after writing the story that we remembered that the inspiration for that conversation came from a short story in Daniel Poliquin’s collection, Le Canon des Gobelins.